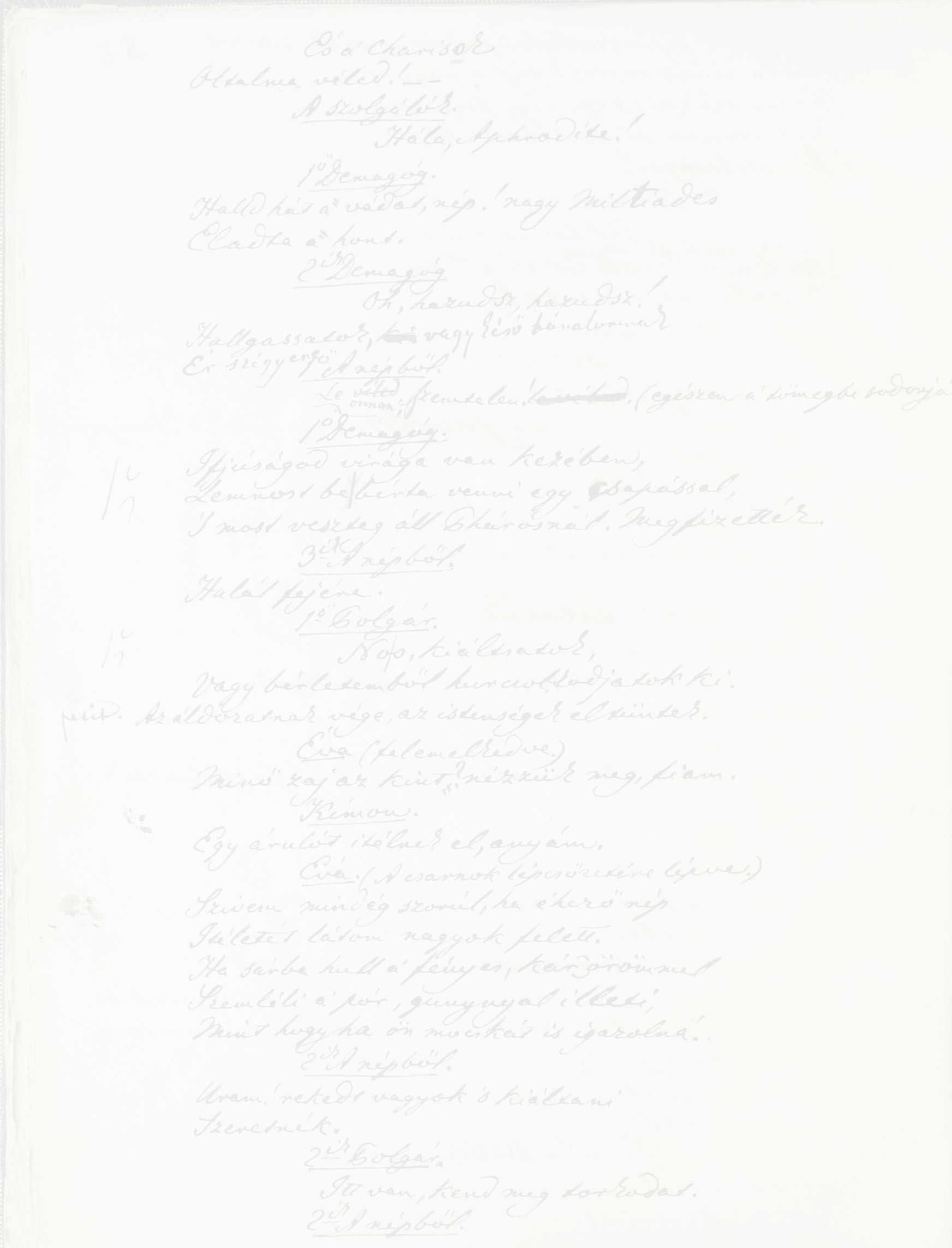

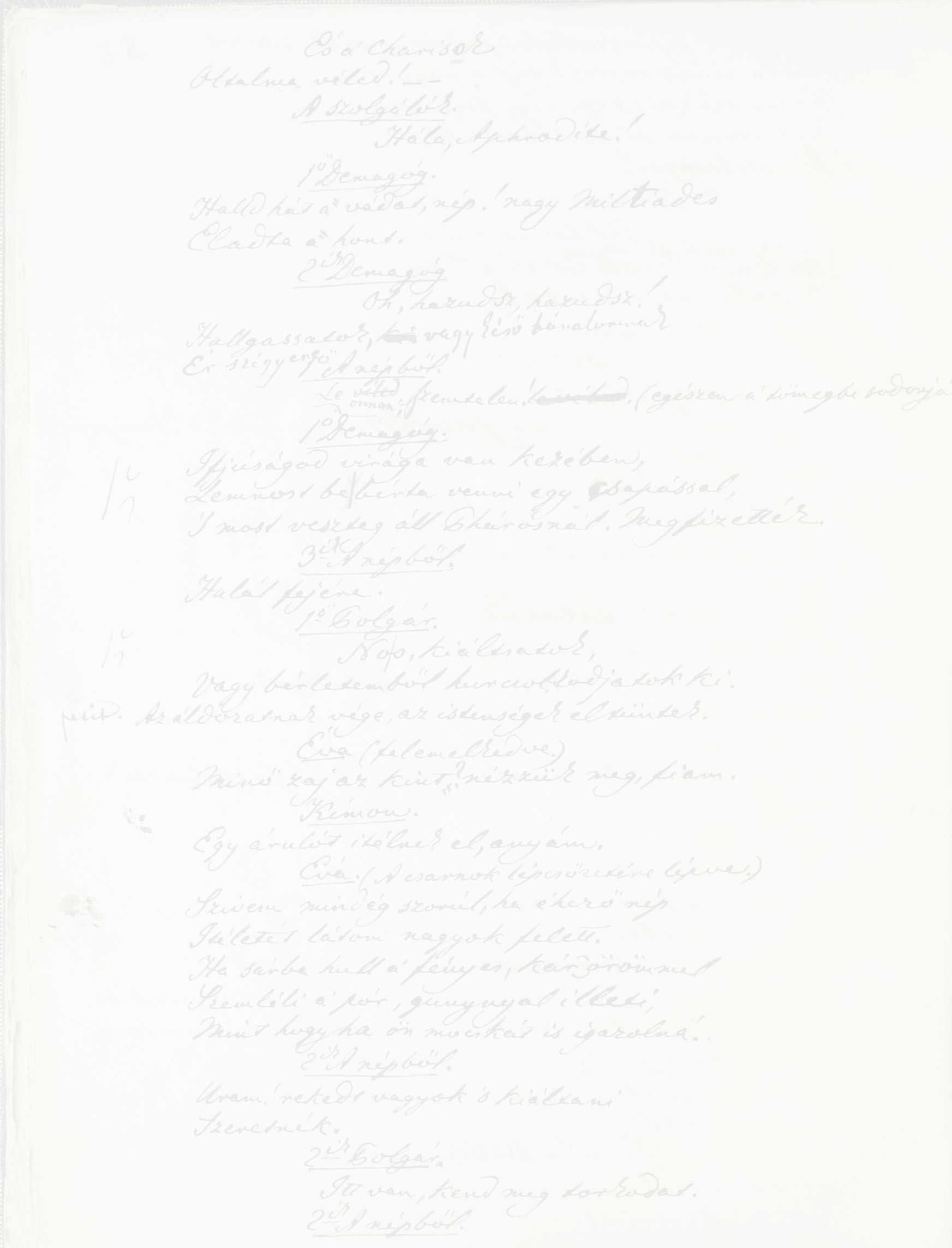

Here lived, created his immortal work »The Tragedy of Man« and deceased

I m r e M a d á c h

x 21. Jan. 1823. † 5. Oct. 1864.

»O Man, strive on, strive on, have faith; and trust!«

Or perhaps you could have this quotation:

»The cause doth live and burns, a glowing flame

To light the world for centuries to come.«

or:

»Tempest when cometh swiftly

Deem my nation is waking,

Making an account and on its soreness

Is its past gone – and future reviving.«

Each of the three quotations reflects Madách’s spirit and the last one is up-to-date from a political point, too… Since I wish to take part in the festivities in Strehová, I kindly ask You, dear Professor to have an official invitation sent to me so that I could get some days off. I agreed with Madách’s great-granddaughter (who is my friend) that we would attend the ceremony together. … (Her grandmother was Jolán Madách, the poet’s daughter) Moreover, I would also like to say a few words on behalf of Erzsike Fráter, and put some flowers (or grasses) from her grave in Oradea on her husband’s grave. To this end, I have already written to my school mate in Oradea, asking her to visit »Li¬dér¬cke«‘s grave in the cemetery in Oradea and send me some flowers or grasses torn off from there in an envelope...

Liptovský Mikulaą, 12 September.”

No one managed to get marble. My father (writes Zoltán Balassa) used to have two marble plates in the castle in Zvolen, with a list of the soldiers from Lučenec who were killed in World War I. A proper piece was cut off this plate and so could the plaque be done, but not using Ibolya Lackóné Kiss’s wording. The inscription on the plaque in Slovak words translates as follows:

Between 1859 and 1861, in this manor house wrote

IMRE MADÁCH

his immortal work,

The Tragedy of Man

on the occasion of the 100th anniversary

of the poet’s death. 1964

A plaque in Hungarian, with the dates of Madách’s birth and death, was placed on the wall of the manor house on 10 October 1995 only, by favour of Csemadok and the Palóc Society.

Returning to the events in 1964: “Zsigmond Hubacsek was commissioned to arrange the material of the exhibition. As the time available was short, the associates of Dom osvety (Culture House) in Banská, namely the group leader Ján Handlovsky and his colleagues rendered help. The works were managed by the painter Zábrady Karol. The costs of the exhibition were also financed by Géza Balassa. His workplace paid 60,000 crowns.

When the local residents became aware of the event under preparation, they offered minor objects which were purchased from them for the exhibition.

It was in the midst of the works, in July 1964 that Mátyás Dráfi, nowadays known as an excellent actor paid a visit to Strehová and reported in the weekly Új Ifjúság [New Youth] that “Madách Museum is on the way”. He had a conversation with the local headmaster Michal Mázor who claimed it was his idea to have the Madách Manor House restored and, to this end, “went round the offices from the LNC to the Slovak National Council”. In response to the reporter’s question if the manor house was to be completed by the anniversary, Michal Mázor replied, smiling and firmly: „Aj keby kamene padali z neba!“ (Definitely, even if stone rain were falling from the sky).

In reference to his former critical article, Béla Balázs this time wrote an appreciative, what’s more, high-spirited report under the title Settled case – Madách Museum soon to open [original title: Elintézett ügy – Rövidesen megnyílik a Madách Múzeum] in Új Szó on 22 August 1964: “Some competent persons did much more for the Madách Manor House and the Madách Museum than we had hoped and the organizers had dared to think about. The issue grew to reach a national scope and lies at our heart… Joining hands, the moral and financial support for the establishment of the museum are so immense, chivalrous and exemplary that only the voice of enthusiasm can describe it. What is currently happening in Dolná Strehová is the most expressive evidence of respecting traditions, friendship between our nations and nurturing the Hungarian-Slovakian cultural ties. This is slightly a kind of memorial, showing what man can reach with benevolence, good intent and by joining hands.”

The contributor summarized the past events and gave an account of the plans for, and actions to be made in, the coming days and weeks. He emphasized the “most extensive” support of SNC, namely that, at his proposal, CNC granted Kčs 300,000 for the works in Strehová. He admired the effective help from the museum in Balassagyarmat and, evidently, the efforts of the “literary people, Csemadok members, teachers and others from Lučenec“.

On 19 September 1964 the Educational and Cultural Section of DNC in Lučenec discussed and approved the proposal for a decision put forward by the Chairman of the Committee Milan Králik, wherein the works done so far were taken cognizance of and the program of the October festivities was finalized:

„The DNC Council takes cognizance of the report on the memorial ceremony held on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of Imre Madách’s death, approves that and the proposed actions, and commissions

1. the DNC Planning Section to grant Kčs 50,000 to complete the renovation of the Madách Manor House in Dolná Strehová and another Kčs 50,000 to remove the dust from the access road to the Manor House. Term: prompt. Responsible official: comrade Michál;

2. determines the composition of the delegations to the memorial ceremonies as lain down in the report;

3. the DNC Planning Section to apply for Kčs 150,000 from the Central Slovakian CNC for 1965 and a worker’s approval of the establishment of the Museum of Hungarian-Slovak Revolutionary Traditions. Term: 15 October 1965. Responsible official: Head of Section comrade Michál.

Approves

the long-term plan of establishing a Museum of Hungarian-Slovak Revolutionary Traditions (of Slovakian competence) in Dolná Strehová.“

The report underlying the decisions summarizes the precedents of the memorial ceremony including a special assessment of Imre Madách’s importance, and it details the programs of the two-day ceremony:

„5 October will mark the 100th anniversary of the day when the world-famous author Imre Madách died in Dolná Strehová where he was born, where he worked and wrote his most outstanding work The Tragedy of Man which earned him worldwide renown.

The manor house of the Madách family in Dolná Strehová, where he was born, where he lived a part of his life and where he died, has been in a rather neglected state in recent years.

Madách is indeed of outstanding importance and, following the cultural convention between the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic and the People’s Republic of Hungary and based on an agreement between the Slovak Authors’ Society and Csemadok, becoming events will be held on the centenary of his death, such as the opening of Madách memorial rooms and a memorial ceremony on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of his death.

CNC granted Kčs 200,000 for the repair of the Madách Manor House. DNC in Lučenec, supported by the Modrỷ Kameň-based division of the Lučenec District Construction Company carried out the renovation works on the manor house. LNC is in charge of fencing off the site, whereas the basic school in Strehová agreed to arrange the park.

The Educational and Cultural Section of DNC made arrangements for collecting various objects for the memorial rooms, repairing some of the furnishings of the Madách family and furnishing the exhibition rooms in the Manor House.

The scenario of the memorial room was made by an associate in the District Centre of State Monument Protection comrade Géza Balassa and is implemented by the District-level Educational and Cultural Section of DNC (comrade Hubaček).

The following program is proposed to be held during the commemoration:

3 October 1964 (Saturday) – Lučenec – 7.00 p.m.

Plant-based club of the trade union of Poµana Opatová (textile shop).

Ceremonial eve in memory of Imre Madách. Opened by the Chairman of the Educational and Cultural Section of DNC in Lučenec. Ceremonial speech delivered by the leader of the delegation from the Slovak Authors’ Society. Welcome speech delivered by the leader of the delegation from the Hungarian Authors’ Society. All other parts of the program are organized by the Lučenec District Centre of Popular Culture. Performers include members of the DJGT Theatre in Banská Bystrica, the quintet from the District Symphonic Orchestra and the Komarno-based Hungarian Regional Theatre. The program lasts 90 minutes. Later, Béla Balázs made a report on this program in the 1964/12 issue of the paper Népművelés [Popular Culture] published in Bratislava: “We expected to experience an exceedingly nice and memorable program where the top rank of our national art pays homage to the person of utmost prominence in world literature and where we establish a museum to erect a memory of Slovak-Hungarian friendship… But, sadly enough, the program was not up to our expectations. It was a sour pill which we however swallowed and forgot.”

4 October 1964 (Sunday), in Dolná Strehová

11.00 a.m. – Parade to Imre Madách’s memorial (representatives of organizations)

Wreathing the memorial

Speech by the Chairman of the Educational and Cultural Section of CNC in Banská Bystrica comrade Jozef Baláľ

Memorial speeches by the representatives of the Slovak and Hungarian authors’ societies.

12.00 a.m. – Ceremonial opening of Imre Madách’s memorial rooms by the Chairman of the Educational and Cultural Section of CNC comrade J. Baláľ.

Visiting the memorial rooms.

2.00 p.m. – Cultural program. Performer: “Urpín” ensemble from Banská Bystrica.

Commemoration traced by: Czechoslovakian television, radio, film and cultural periodicals.

The district weekly Pokrok reported on the completion of the renovation works in Dolná Strehová and on the soon-to-open museum which is to “exhibit mainly the works that were born during Madách’s stay in Slovakia” on 2 October. According to the correspondent the Madách Museum “will also be enriched by exhibits from museums in Budapest” and “will be opened in honour of the 20th anniversary of the liberation on 9 May 1945 of our country” (…) Below a picture of the Madách cenotaph, Madách’s appreciation related to the DNC decision, included in the report and quoted above, was also published on the front page of the paper.

It was similarly on 2 October that a picture report was published in Új Szó, under the title Dolná Strehová prepared. Madách Museum to open on Sunday [original title: Alsósztregova felkészült. Vasárnap nyitják meg a a Madách-múzeumot] and written by Béla Balázs who had been continually focusing on this issue: “The desire, the old plan has been fulfilled, Madách Museum is now under roof. The event meets with everyone’s joy and unanimous recognition.”. After his earlier criticism, the journalist this time uses appreciative words as he writes about everybody: about SNC, the Central Slovakian CNC which granted Kčs 300,000 for this purpose, about LNC that rendered all help, the locals in Strehová who worked hundreds of hours and, last but not least, the literary enthusiasts in Lučenec who did not merely make plans but were with hard diligence collecting the materials, negotiating with the competent officials, organizing the preparatory works, giving advice and offering technical assistance.

„Madách Museum was realized as a result of the Hungarians’ and Slovaks’ exemplary teamwork. It expresses that our nations did not and do not only live together but they jointly maintain and nourish the progressing traditions” – writes Béla Balázs in his closing words.

The 10 October issue of the Lučenec district weekly (published in Hungarian) Haladás [Progress] reported on the grandiose event under the main title Elevating Madách festivities [original title: Felemelő Madách ünnepségek] and the subtitle Madách Museum opened in Dolná Strehová [original title: Madách Múzeum nyílt Alsósztregován]. “The ancient Madách manor house was in its rejuvenated state, expecting to welcome the good many guests coming from within and outside the country” – wrote the correspondent who emphasized that “the cultural representatives of the inland Hungarians also contributed” to the official speeches and that “our district has been enriched with fairly significant cultural values through the establishment of the Madách Museum… and it will attract thousands of visitors. The opening of the museum is also a sign to confirm that Hungarian-Slovak cultural relations are getting deeper and deeper, stronger and stronger and that the two nations mutually respect and appreciate the other’s great men.”

A detailed and subjective personal account, written by Péter Ruffy, was published in the 6 October 1964 issue of Magyar Nemzet [Hungarian Nation]:

„Everyone wore dark festive holiday dress. A flower-garden breathed forth perfume at the head of the column: Hungarian, Slovak, Slovakia-resident Hungarian pioneers and children were bringing their wreaths. Roses, dahlias, sword-lilies were flitting in the bosom of the wreaths; there were late carnations, the last flowers of autumn among the leaves of the ferns in the wet bunches of wild flowers. The first wreath was sent by the co-operative in Csesztve, Hungary, the second is being taken by students from Kossuth Secondary Grammar School in Sárospatak, the third by Slovak pioneers, the fourth by the students of the Hungarian language secondary grammar school in Vel’ké Kapuąani, Czechoslovakia. The wreaths of Czech and Slovak writers, the Slovak National Council, the Hungarian Authors’ Society in Slovakia, CSEMADOK, the district-level National Council, the Hungarian and Slovakian schools are coming in endless rows.

There is a festive procession walking behind the wreaths. The Hungarian Peace Council is represented by Árpád SZAKASITS and Ernő MIHÁLYFI, and the Hungarian Authors’ Society by József DARVAS and Károly JOBBÁGY. The President of the Slovak Authors’ Society and university professor in Bratislava dr. Milan PISUT is walking beside the President of the Hungarian Authors’ Society, followed by the Secretary General of CSEMADOK Rezső SZABÓ and the editor-in-chief of Irodalmi Szemle [Literary Review], a paper published in Bratislava in Hungarian, László DOBOS. The cars of the Hungarian Radio and the Slovakian television are queued at the two sides of the procession. Wherever you look, you see brisk film reporters and press correspondents.

The celebrating crowd is streaming through the garden gate of the beautifully restored Madách Manor House in Strehová into the old English park and further on, among the wattle and oak trees in the garden and along the road freshly topped with gravel, to the cenotaph whose stone slabs the Madách ancestors and the poet rest below. The picture is clear and light: the hill among the wattles is covered by a forest of people. Thousands of colours flare up in the frames of the green or turning-to-yellow nature: the white, red and pink colours of the flowers, the varicoloured dresses, the pioneers’ red scarves, the festive black clothes. The male genius (a work by the Bratislava-resident sculptor Alajos RIGELE) almost seems to be flying in the light autumn times on the top of the cenotaph. The wreaths will soon cover the memorial. A marvellous blue-eyed and bow-backed woman, Madách’s great-granddaughter Alice FITZEKNÉ REINHARDT who has come from Banská Bystrica steps in front of the grave wearily and weakly. Her daughter and grand-child (who is Madách’s great-great-great-grandchild) are also with her. The three late offshoots of the Madách family place a single wreath on the grave.

The workers’ choir from Zvolen performs Slovak and Hungarian folk songs: the brazen and fruity voices embrace the grave and they slowly go past and fly away from the valley of small Strehová brook.

There is a high podium in the valley facing the WREATHED cenotaph, with a huge expanded white canvas curtain behind the podium, showing the last row of the Tragedy in Slovak and Hungarian. The postulate »Man, strive on« urges the fraternization of the nations above the light green Strehová fields in this very moment. Further on, Madách’s message of »have faith; and trust« promises a success in this strife. The Chairwoman of the Slovakian Madách Committee Mária LICSKOVA, the representative of the Slovak National Council Eng. Jozef PRINTZ and university professor in Bratislava and the President of the Slovak Authors‘ Society dr. Milan Pisut all welcome the brotherhood of nations.

The President of the Hungarian Authors’ Society József Darvas is, as he expressed in the beginning of his speech, »standing in front of Madách’s grave with earnest emotions« and thanks the Slovak National Council for »this splendid ceremony«.

“After the misunderstandings and hardships of long centuries, more cheerful and nicer days rise up; we no longer live merely beside each other but begin to live together.”

Ernő Mihályfi first quoted the words of the MP Madách which the latter used to address to his Slovak speaking electors. Then he explained that a proceeding was held on the Madách issue in the Hungarian Academy of Sciences in the beginning of the fifties and a question was raised there: is Madách’s work suitable for strengthening the peace camp, for helping the mutual recognition and cooperation of nations striving for peace and progress? Does he belong to our wealth that the Hungarian nation can enrich the treasury of international socialist culture with? A decade has almost gone by and time has given a definite answer to this question. The World Peace Council proposed to celebrate the Madách centenary, a major anniversary affecting mankind, all over the world.

In his stately speech, the editor-in-chief of the Bratislava-published Irodalmi szemle László Dobos called this ceremony the »peak point« of our socialist development wherefrom, if one looks back, one can review all the faults of the near past. The Secretary General of CSEMADOK Rezső Szabó quoted Ádám’s word about the faith of life.

Afterwards, we walked over to the beautifully restored double-tower old Madách manor house which was blooming in light colours. On behalf of the Banská Bystrica district party committee and the district-level National Council in Banská Bystrica, it was Josef BALAS who opened the museum at the main entrance: >We oblige ourselves – he said in Slovak language, among others, – that we will care for this museum as if Imre Madách had been the son of our own nation.<

The MUSEUM was presented to the public in Hungarian and Slovak by an elderly associate in the Banská Bystrica museum Géza BALASSA.”

According to Géza Balassa’s report in a periodical focusing on monument protection, the rooms opened to the general public looked as follows: the room (called room 1, which was the big hall that the Madách family used to call the palace) exhibits the poet’s and his family’s pictures and personal documents, as well as Madách’s early works. The cards in room 2 documented the beginnings of activities in county-level public life. Room 3 visualizes 1848-49. Imre Madách’s head sculpture, a work by Ferenc Sidló, and the latest illustrations to the Tragedy were exhibited in room 4. The next room was wholly dedicated to Madách’s main work: the various publications and translations of the Tragedy were put in exhibition cases. Some duplicates of Mihály Zichy’s illustrations are likewise on show here. Room 6 vivifies the theatre premieres.

The seventh furnished room (the so-called Den of Lions, using Géza Balassa’s words) is “filled with contemporary furniture, and the walls eradiate the air of the past centuries; the visitor comes to feel that the poet who had the future of mankind so much at his heart is also here with us today”.

The weekly of Csemadok A Hét [The Week] was published on the day of the ceremony in Strehová, with a front page showing the sculpture of Ádám standing on the cenotaph. The poet Árpád Ozsvald commemorated Imre Madách. A lyric description is given in the introduction to his article: “The foliage of the centuries-old trees turns from yellowish green into greenish brown. These elderly guards of the Strehová park rarified as time went by. The small manor house has rejuvenated by the grandiose anniversary. It has been painted outside and inside, the decayed parquetry and door-posts have been replaced by new ones. Still, everything radiates the spirit of the great poet who died one hundred years ago.”.

It was the 25 October issue of A Hét that reported on the commemoration itself. In addition to describing the venue and the events, it emphasized that “The ceremony… lived up to the poet and the heritage. Thousands were gathering in the street of … Dolná Strehová to pay a tribute to the memory of Madách … they speak Hungarian, Slovak, Czech, but they all claim intellectual heritage … The spirit of human creative power and originative desire moved in the vaulted room of the manor house which became a Madách museum.” The contributor Gyula Duba interpreted József Darvas’s words (already quoted by Péter Ruffy – “finally begin to live together”) as Madách’s legacy that can demolish historical prejudice.

In its 8 November issue, A Hét published Béla Balázs’s interviews (made on 4 October) under the title Madách Museum – the monument of friendship [original title: A Madách Múzeum – a barátság emlékműve]:

“I’m filled with the zest of victory. I’m happy that my plan could become true in a bigger scope than I had originally thought about. I’m also happy that I could give my collection to the museum” – said the ex-teacher in Strehová and memory guard Zoltán Batel.

„I knew“ – declared József Darvas – “that Madách would be commemorated in Strehová, too, but I didn’t think that the ceremony would be that big. I fairly like the museum, it surpasses my expectations by far.”.

According to the 76-year-old politician Árpád Szakasits “The Madách Museum is the symbol of Czechoslovakian-Hungarian friendship … I consider the gathering the festive of brotherhood where the flower of a new spring has effloresced. I would like this flower never to fade.”

Béla Balázs also asked Madách’s great-granddaughter Alíz Fitzekné Reinhardt to say a few words: “I used to spend a lot of nice hours here in my childhood. I’m moved now that I could return to Strehová. Everything is very nice and I think an incredible work has been done here. I thank you kindly.”

The librarian in Lučenec Ferdinánd Ferencz and the teacher in Fil’akovo Dr. Lajos Lóska also had a major share in creating the museum. The former declared “The struggle was not in vain, the museum is nicer than we had thought.”. According to the latter “The opening of the museum is a milestone in our cultural life and it commits us to a lot of things”…

The Chairman of the Educational and Cultural Section of DNC in Lučenec Milan Králik talked about the future and the plans: „The empty rooms of the manor house will host a Mikszáth museum and we will open a permanent exhibition on Slovak-Hungarian literary and historical relations.”

Finally, this permanent exhibition was not realized, but later on Mikszáth mementos and placards introducing the Slovak personalities of the region were indeed placed in the Strehová manor house.

The quoted contemporary documents and even some personal mementos suggest that the festivities had some flaws and were subject to ideological ballasts. Imre Madách must have turned round in his grave after some puffed-up statements in recent politics. Later on it turned out that there were also some architectural problems because after almost two decades the manor house had to be closed, and only in the 21st century did the manor house in Dolná Strehová become and will it continually be a worthy and up-to-date Madách memorial site in terms of both content and technicalities.