After the defeat of the War of Independence, in August 1849 the

operation of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences was banned by the imperial

government. Fron then on for nearly a decade the scholarly institution could

only exert a limited activity. They could not have public events or general

meeting, and consequently could elect no new members. A condition to start full

operation again was to adopt a new statute, in which they recognize the

authority of the ruler and the control of the authoritarian government. (The

Hungarian Academy of Sciences was founded as a national collaboration, on the

initiative of István Széchenyi, in this respect it was an exception among the

great academic institutions of the period, usually founded by rulers.)

In

1858 the new statue was forced on the Academy, thus it could start its full

operation with a general assembly and with the election of almost a hundred new

members.

The following years were those of peaceful scholarly work. In 1863, the year of

the election of Imre Madách a member of the Academy, the historian László Szalay,

general secretary of the Academy could proudly enumerate the scholarly results

of the past year, the volumes published with the collaboration of the five

permanent academic committees, the scientific results, the Corvinas discovered

in Istanbul, the Central Asian research of Ármin Vámbéry

1

The then existing statute did not require the preparation of the member

recommendation in the modern sense, that is, a detailed explanation of the

candidate’s biography and scientific results. In contemporary usage, one or more

voting members of the Academy presented a name or even a list to the respective

scientific class; at the meeting of the class it was discussed, and they

submitted the approved names to the electing general assembly. The HAS had six

classes at the time, Class I (Language and Fine Sciences) also included writers

and other artists. According to §. 29 of the statutes, the scientific classes

could recommend such scholars and authors for corresponding members who have

already proved with their oeuvre that they are suitable to realize the goals of

the Academy.

2

In 1863, the Language and Fine Arts Departments presented their recommendations

in one sheet. The submission was drafted by Zsigmond Kemény, a honorary member

of the Academy, and it was also signed by Ferenc Toldi, Pál Hunfalvy, Gábor

Fábián, János Arany, János Nagy and Mór Ballagi.

3

In 1863, the Language and Fine Arts Departments presented their recommendations

in one sheet. The submission was drafted by Zsigmond Kemény, a honorary member

of the Academy, and it was also signed by Ferenc Toldi, Pál Hunfalvy, Gábor

Fábián, János Arany, János Nagy and Mór Ballagi.

3

They recommended in the first place the composer Count Leó Festetics, and in the

second Imre Madách, member of the Kisfaludy Society, the eminent author of

The tragedy of man. The six candidates also include Ferenc Erkel, “due to

his great merits concerning national opera”. He was nominated several times, but

never elected among the members of the HAS.

They recommended in the first place the composer Count Leó Festetics, and in the

second Imre Madách, member of the Kisfaludy Society, the eminent author of

The tragedy of man. The six candidates also include Ferenc Erkel, “due to

his great merits concerning national opera”. He was nominated several times, but

never elected among the members of the HAS.

In January

1863 they held the 24th general assembly of the HAS, and on the 12 January

meeting they elected the members. The ordinary and honorary members (at that

time the corresponding members had no right to vote), thirty-seven in all,

secretly cast their votes. According to the protocols, Imre Madách was elected

in the first place, with 32 votes and 3 against, a corresponding member of the

Academy in the Class of Language and Fine Arts. Apart from him, Miklós Szemere

and József Lévay received enough votes.

4

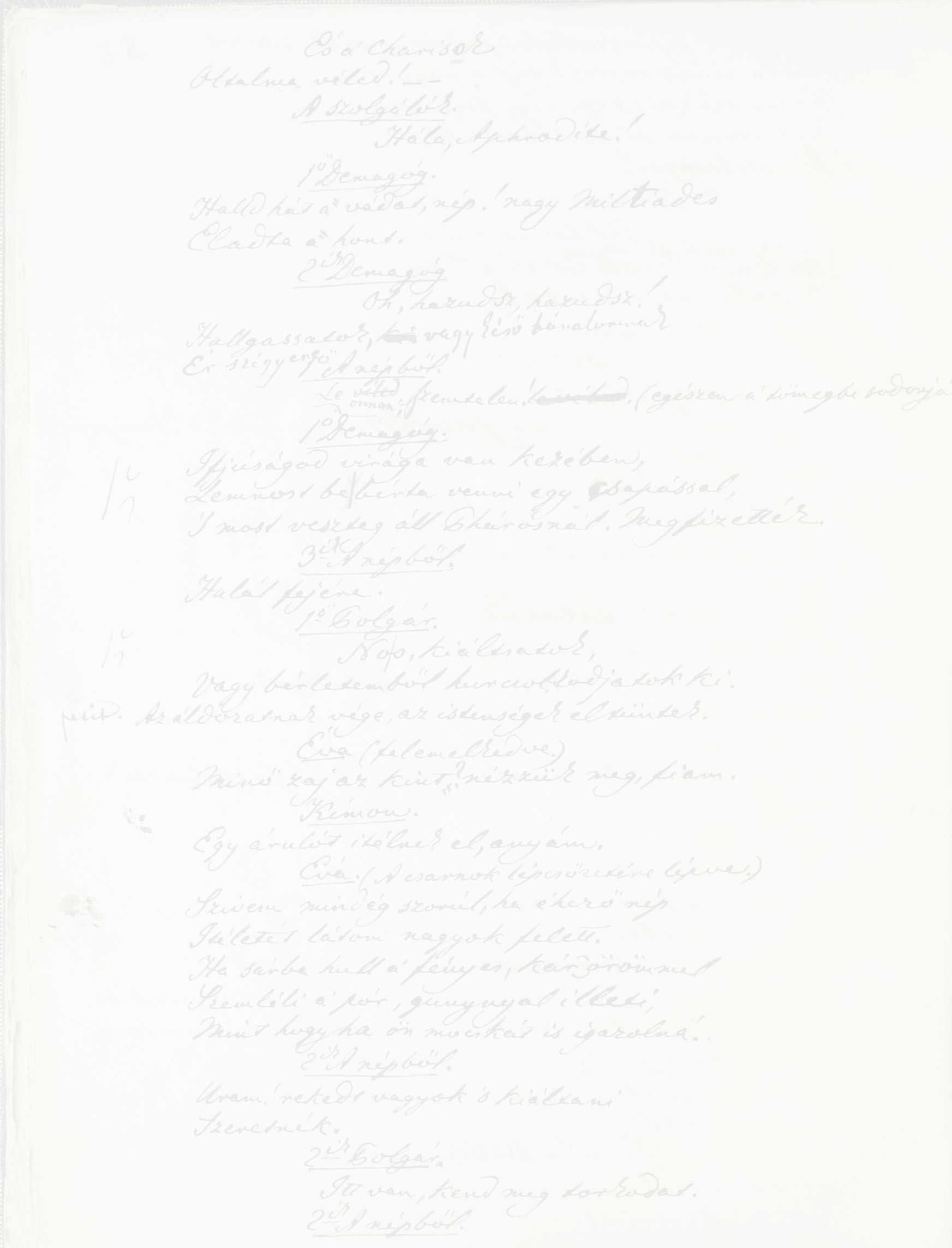

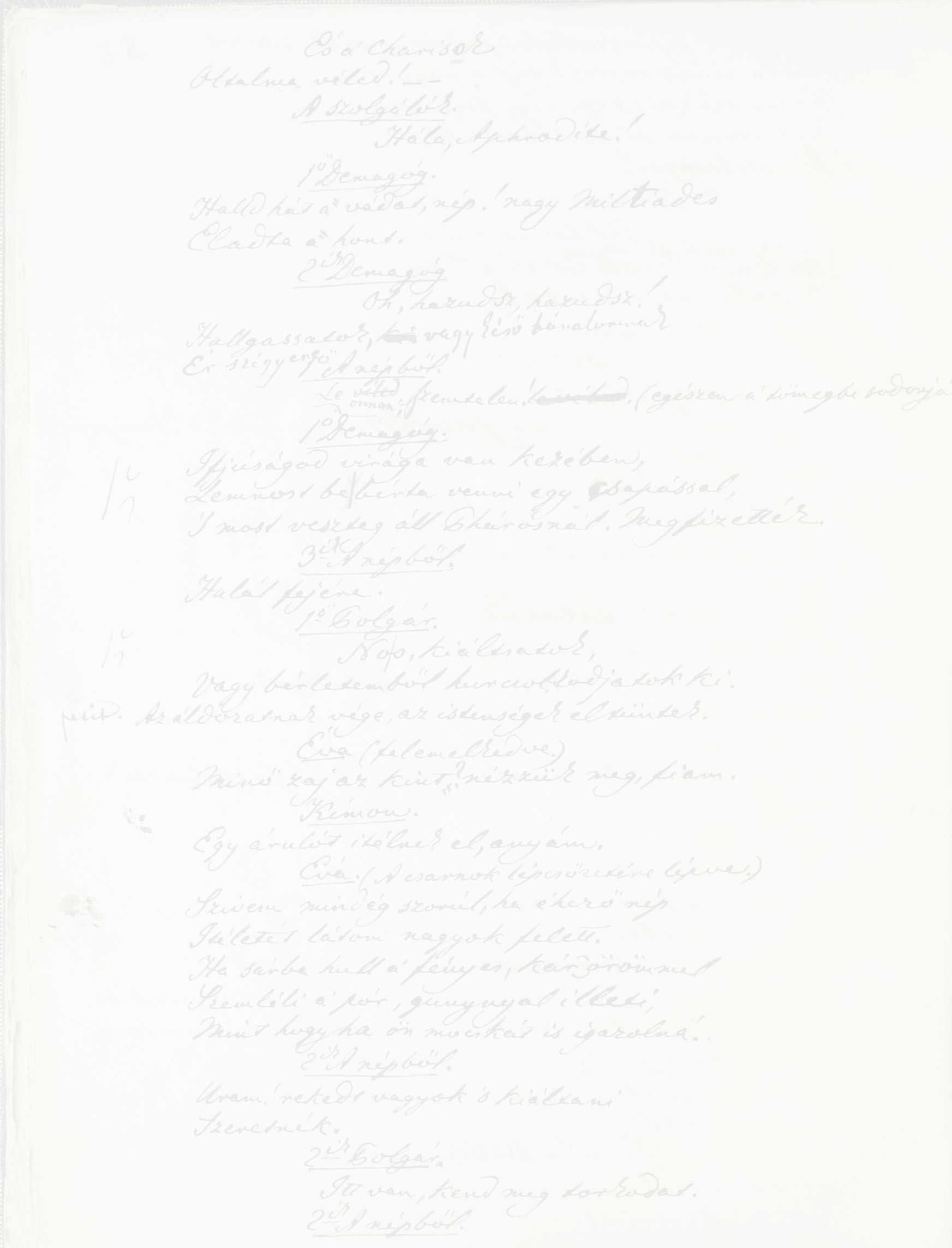

In the 18 April 1864 meeting of the Class of Language and Fine

Arts, corresponding member Károly Bérczy read the inaugural dissertation of the

ill Imre Madách, with the title On the woman, especially in aesthetic respect.

5

The meeting was presided by Emil Dessewffy, president of the HAS, and the

members appeared in a rather large number, more than thirty.

6

The at first sight surprising title introduces a dissertation, in which Imre

Madách discusses the different roles of men and women, and – in Madách’s words –

explores the disadvantages of when the woman quits her traditional social and

gender role. According to Madách, the physical difference between the two

genders also appears in the intellectual field. The guiding principle of his

inaugural speech is often quoted as a commonplace: “The woman evolves earlier,

but never arrives at a complete male maturity; she understands and learns

easier, but in lack of a creative genius she can never rise among the guiding

spirits of mankind.” This nowadays astounding claim was generally accepted

in the period. Madách, who was interested and knowledgeable in natural sciences,

certainly read the study of Pál Almási Balogh – honorary member of the HAS, a

famous physician of his age, who treated Lajos Kossuth and accompanied Széchenyi

to Döbling as the doctor of the family –,

7

and in some places his impact can be detected in his essay. In his study,

published in several parts, the prominent physician claimed on the basis of

natural scientific arguments that women, due to their biological and physical

features, lack the conditions of attain deeper thinking and rising into higher

spheres of intellectual world.

Szándéka szerint a székfoglaló nem a nők alacsonyabb rendűségét kivánja

bizonyítani. Amint a természet is sokszínű, a férfi és nő között sincs merev

válaszfal – írja Madách. Születhetnek olyan nők, akik magas szellemiségükkel

felülemelkednek nemük korlátain, s egyenrangúvá válnak a férfiakkal – s tegyék

is azt, mondja Madách –, de ezzel lemondanak nemük mindazon előnyeiről, amik

nőként ragyogóvá és boldoggá teszik őket.

Madách szerint a férfi és a nő közötti különbség figyelembe nem vétele, azaz, ha

valaki a női emancipációt hirdeti, nagyon tévesen cselekszik, s aligha tesz jó

szolgálatot azoknak, akiknek kedvezni akar.

Legyen a nő egyenlő a férfival jogban, tiszteletben pedig álljon felette. De ne

éljen a nő jogaival végletekig (azaz ne lépjen ki a hagyományos női szerepből),

s gesztusának kedves viszonzása lesz azon hódolat, mellyel a férfi maga fölé

emeli – fejezi be gondolatmenetét az író.

Madách meglehetősen hosszú dolgozata 1864 nyarán jelent meg három folytatásban

Arany János hetilapjában, a Koszorúban. Nyilvános vitát nem keltett, de Veres

Pálné, Madách Imre régi ismerőse, plátói szerelme és

szellemi partnere 1864 kora őszén két levelet is intézett az íróhoz, tiltakozva

sommás megállapításai ellen. Ezek a levelek vagy

levélfogalmazványok – nem tudjuk, hogy eljutottak-e Madách Imréhez – eltűntek az

idők folyamán, csak Veres Pálné életrajzi kötetéből ismerjük tartalmukat.

8

Veres

Pálnét elsősorban az a megállapítás döbbentette meg, hogy a nő soha sem

emelkedhet a férfi szellemi színvonalára. Az egyik levélben a nők helyzetét az

észak-amerikai fekete rabszolgákéhoz hasonlította (ekkor zajlott az amerikai

polgárháború), s kijelentette, hogy a rabszolgatartáshoz hasonlatos azon

gondolkodásmód, amelyik a női nemet kizárólag a mechanikus tevékenységre

szorítaná. Szenvedélyesen cáfolja, hogy a nőt a természet kevesebb szellemi

tehetséggel ruházta volna

föl. Úgy gondolja, gyakorlat teszi a mestert, aki tanul, gondolkodik,

kísérletez, fejleszti magát a tudományokban, szép eredményre juthat, legyen az

férfi vagy nő.

Madách meglehetősen hosszú dolgozata 1864 nyarán jelent meg három folytatásban

Arany János hetilapjában, a Koszorúban. Nyilvános vitát nem keltett, de Veres

Pálné, Madách Imre régi ismerőse, plátói szerelme és

szellemi partnere 1864 kora őszén két levelet is intézett az íróhoz, tiltakozva

sommás megállapításai ellen. Ezek a levelek vagy

levélfogalmazványok – nem tudjuk, hogy eljutottak-e Madách Imréhez – eltűntek az

idők folyamán, csak Veres Pálné életrajzi kötetéből ismerjük tartalmukat.

8

Veres

Pálnét elsősorban az a megállapítás döbbentette meg, hogy a nő soha sem

emelkedhet a férfi szellemi színvonalára. Az egyik levélben a nők helyzetét az

észak-amerikai fekete rabszolgákéhoz hasonlította (ekkor zajlott az amerikai

polgárháború), s kijelentette, hogy a rabszolgatartáshoz hasonlatos azon

gondolkodásmód, amelyik a női nemet kizárólag a mechanikus tevékenységre

szorítaná. Szenvedélyesen cáfolja, hogy a nőt a természet kevesebb szellemi

tehetséggel ruházta volna

föl. Úgy gondolja, gyakorlat teszi a mestert, aki tanul, gondolkodik,

kísérletez, fejleszti magát a tudományokban, szép eredményre juthat, legyen az

férfi vagy nő.