Imre Madách passed away on 5 October 1864, and he was buried on 7 October in the

modest family tomb in Alsósztregova.

1 In 1909 Nógrád county decided to erect a memorial worthy to their

great son. The county’s general assembly offered 1000 crowns for the purpose,

and in addition they launched a national collection for a grave suitable to pay

tribute to the great author. Collection sheets were also sent out with the call.

2 The collection, however, was unsuccessful, and then the world war

and the

borders redesigned by the peace treaties overshadowed the case for some time.

Imre Madách passed away on 5 October 1864, and he was buried on 7 October in the

modest family tomb in Alsósztregova.

1 In 1909 Nógrád county decided to erect a memorial worthy to their

great son. The county’s general assembly offered 1000 crowns for the purpose,

and in addition they launched a national collection for a grave suitable to pay

tribute to the great author. Collection sheets were also sent out with the call.

2 The collection, however, was unsuccessful, and then the world war

and the

borders redesigned by the peace treaties overshadowed the case for some time. The president in his response to the greetings of the locals anounced, that he

respects Madách not because he was of Slovak origin, but because he sought the

man in the man. Although the next day in Losonc, at the reception of the

deputies of the local Hungarians he spoke about Madách as a Hungarian poet, the

words of President Masaryk aroused great indignation in the Hungarian public

opinion. The situation caused by poor drafting could not be improved by the fact

that the old president – according to press reports – spoke in Hungarian in a

Hungarian environment. The Pesti Hírlap rejected the claim in an editorial.

4

The historian Lajos

Gogolák, an expert of Slovak literature and history, refuted Madách’s Slovak

identity in a data-rich study in the November 1930 edition of Magyar Szemle.

5

However, we can claim with certainty that it was the presidential visit and its

press coverage which turned the attention to the abandoned and neglected grave

of the great author.

The president in his response to the greetings of the locals anounced, that he

respects Madách not because he was of Slovak origin, but because he sought the

man in the man. Although the next day in Losonc, at the reception of the

deputies of the local Hungarians he spoke about Madách as a Hungarian poet, the

words of President Masaryk aroused great indignation in the Hungarian public

opinion. The situation caused by poor drafting could not be improved by the fact

that the old president – according to press reports – spoke in Hungarian in a

Hungarian environment. The Pesti Hírlap rejected the claim in an editorial.

4

The historian Lajos

Gogolák, an expert of Slovak literature and history, refuted Madách’s Slovak

identity in a data-rich study in the November 1930 edition of Magyar Szemle.

5

However, we can claim with certainty that it was the presidential visit and its

press coverage which turned the attention to the abandoned and neglected grave

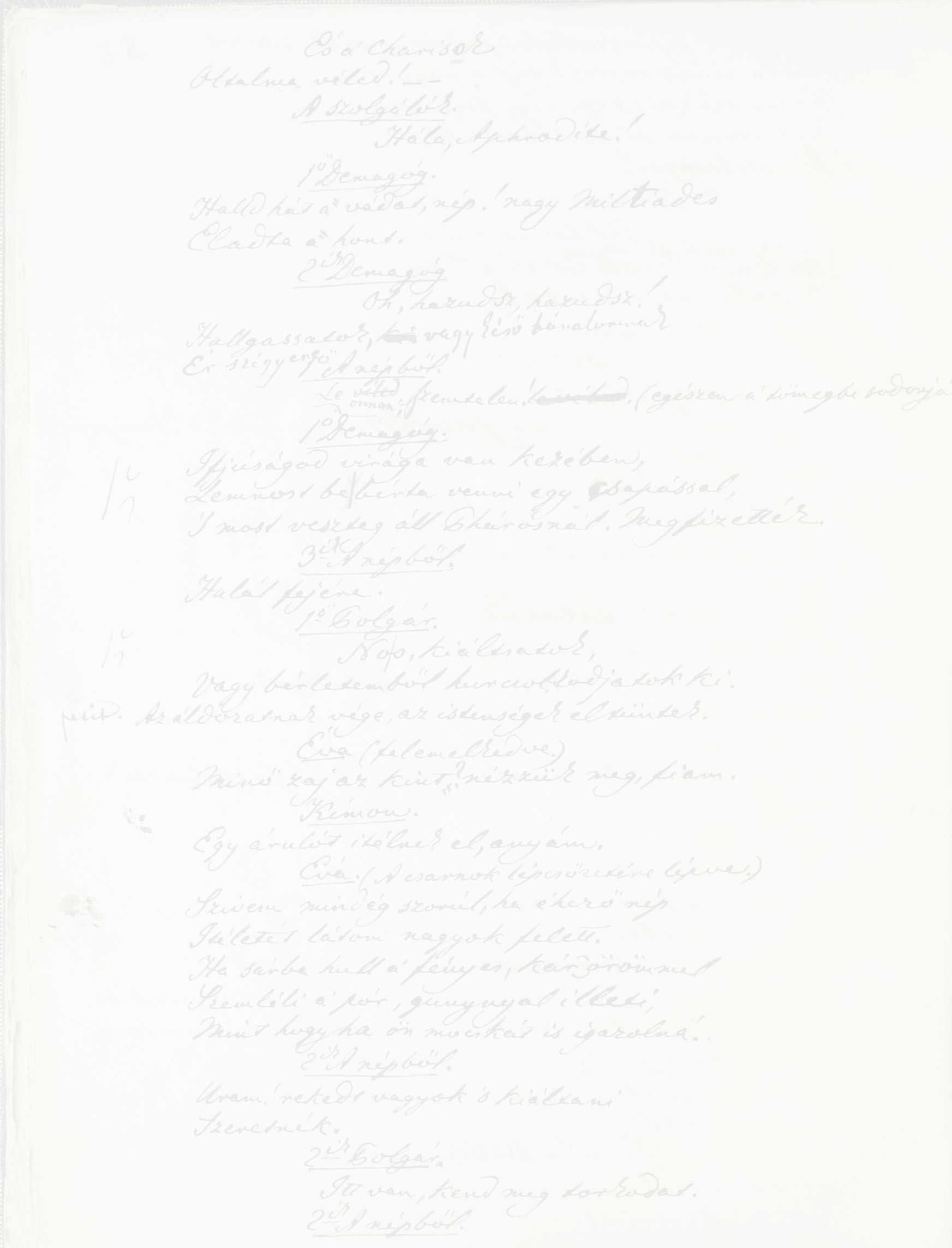

of the great author. Zsolt

Harsányi, who was just writing a biographical novel on Imre Madách, visited

Alsósztregova in the summer of 1932, and published an article on the grave with

the title Wreaths in the Madách crypt.

6 In the small Catholic cemetery he found a very simple, whitewashed

and shingle-roofed building. The rusty lock of the door could be opened only

with the help of locksmiths. Inside, a simple stone table-altar, in the vault

beneath the floor are buried the members of the Madách family. The side wall of

the vault had collapsed during an earlier funeral, and one could see the

coffins, all in very poor conditions. Next to the great poet lay his mother, his

son Aladár Madách, the wife of the latter, and the unidentifiable remains of the

earlier deceased family members. Above the stone table, the dried relics of

piety: the wreaths of President Masaryk and his daughter.

Zsolt

Harsányi, who was just writing a biographical novel on Imre Madách, visited

Alsósztregova in the summer of 1932, and published an article on the grave with

the title Wreaths in the Madách crypt.

6 In the small Catholic cemetery he found a very simple, whitewashed

and shingle-roofed building. The rusty lock of the door could be opened only

with the help of locksmiths. Inside, a simple stone table-altar, in the vault

beneath the floor are buried the members of the Madách family. The side wall of

the vault had collapsed during an earlier funeral, and one could see the

coffins, all in very poor conditions. Next to the great poet lay his mother, his

son Aladár Madách, the wife of the latter, and the unidentifiable remains of the

earlier deceased family members. Above the stone table, the dried relics of

piety: the wreaths of President Masaryk and his daughter. On the summer of

1932 the historian and financier Lajos Horánszky (1871–1944), ordinary

member of the Kisfaludy Society and a great admirer of Imre Madách visited

Alsósztregova, and saw with his own eyes the terrible conditions of the grave.

On the summer of

1932 the historian and financier Lajos Horánszky (1871–1944), ordinary

member of the Kisfaludy Society and a great admirer of Imre Madách visited

Alsósztregova, and saw with his own eyes the terrible conditions of the grave.

The Madách descendants, Imre Madách’s granddaughter Flóra, her husband dr Pál

Lázár and their daughter lived in rather poor conditions in the Madách castle of

Alsósztregova. The estate was burdened with a huge mortgage: it was obvious that

the family will not build a new grave with their own effort.

The Madách descendants, Imre Madách’s granddaughter Flóra, her husband dr Pál

Lázár and their daughter lived in rather poor conditions in the Madách castle of

Alsósztregova. The estate was burdened with a huge mortgage: it was obvious that

the family will not build a new grave with their own effort. János

Giller (1886–1956), lawyer and Slovak regional deputy said a bold and

straight speech on behalf of the Madách Company of Losonc: the Hungarians living

in “Slovensko” proudly boast with the great poet and thinker as a fellow

Hungarian.

9

János

Giller (1886–1956), lawyer and Slovak regional deputy said a bold and

straight speech on behalf of the Madách Company of Losonc: the Hungarians living

in “Slovensko” proudly boast with the great poet and thinker as a fellow

Hungarian.

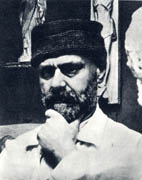

9  Alajos

Rigele studied at the Art Academy in Vienna. In his last school year he won with

the memorial grave of Péter Pázmány the Vilmos Fraknói Award as well as a

two-year study trip to Rome. In 1911 he definitely settled in Pozsony. After the

world war his main source of livelihood were the commissions of the citizens of

Bratislava, about one-sixth of his works are tombstones. The 1930s brought

change in his life, when various associations and institutions also discovered

his work. Rigele worked with a wide variety of materials, stone, bronze, wood,

but according to his monographer Zsolt Lehel his artistic qualities were best

expressed in marble.

10

In his representations he regularly stressed opposites: a frequent motif in his

works are the smooth figures rising from a rough background. He preferred to

stress the contrast of agility and calmness – wrote about him Zsolt Lehel,

who considers Rigele as the most important sculptor of Pozsony.

Alajos

Rigele studied at the Art Academy in Vienna. In his last school year he won with

the memorial grave of Péter Pázmány the Vilmos Fraknói Award as well as a

two-year study trip to Rome. In 1911 he definitely settled in Pozsony. After the

world war his main source of livelihood were the commissions of the citizens of

Bratislava, about one-sixth of his works are tombstones. The 1930s brought

change in his life, when various associations and institutions also discovered

his work. Rigele worked with a wide variety of materials, stone, bronze, wood,

but according to his monographer Zsolt Lehel his artistic qualities were best

expressed in marble.

10

In his representations he regularly stressed opposites: a frequent motif in his

works are the smooth figures rising from a rough background. He preferred to

stress the contrast of agility and calmness – wrote about him Zsolt Lehel,

who considers Rigele as the most important sculptor of Pozsony.

Rigele, who gladly accepted the commission, in early 1936 prepared two models

and sent their photos to Ede Telcs. One of them represents an eagle taking off,

while the other a towerin youngster.

11

The judges, Albert Berzeviczy, Géza Voinovich and Lajos Horánszky (we cannot

call them a jury, as they never officially came together) accepted the second

plan. Horánszky asked the artist to perform the spring survey and submitt he

budget in the spring. The statue should be ready by autumn, so that it could

stand in its place by All Saints’ Day.

12

In early summer

1936 the sculptor already sent a photo on the clay model to Ede Telcs, asking for his professional opinion. As he wrote, he

planned agile drapes, which even symbolically stood in contrast to the relaxed

arch of the body, in which he intended to shape much longing.

13

In early summer

1936 the sculptor already sent a photo on the clay model to Ede Telcs, asking for his professional opinion. As he wrote, he

planned agile drapes, which even symbolically stood in contrast to the relaxed

arch of the body, in which he intended to shape much longing.

13

In May 1936 Alajos Rigele had a site visit in Alsósztregova. He found the grave

in a neglected condition. Due to the careless foundation and masonry the ground

water destroyed it so much that it had to be rebuilt.

In May 1936 Alajos Rigele had a site visit in Alsósztregova. He found the grave

in a neglected condition. Due to the careless foundation and masonry the ground

water destroyed it so much that it had to be rebuilt.

In summer 1936

Rigele and his son, the architect László Rigele undertook the preparation of the

Madách memorial and its installation in site, as well as the necessary

rebuilding of the grave. The statue on the memorial and Madách’s portrait relief

were made of bronze, and the pedestal of a time-resistant green sandstone. In

the design of the memorial, the artist strived after a monumentality expressed

with the simplest tools, as Madách’s personality was also without any artificial

attitude. The statue, or in Regele’s beautiful words, the spirit of the Man

longing for the sky, is standing on top of the grave. The two Rigeles undertook

to control the entire working process. The total cost of the works were

estimated at 53,697 crowns.

We have only limited data on the financing of the memorial. One reason is that

the organizers wanted to preserve the appearance of private initiative.

Lajos Horánszky, the coordinator of the works certainly reported about

them to the Kisfaludy Society, but the documents of the society survived

incomplete, as they were partially destroyed at the turn of 1944/45, during the

siege of Budapest. The costs were probably entirely covered from the funds

collected in Hungary. The largest sum was offered by the Hungarian Academy of

Sciences, which contributed to the erection of the Madách memorial with at least

3700 pengős from the interests of the Baron Podmaniczky Zsuzsanna Foundation.

18

The other sources are still unknown, or waiting for exploration.