Although the cover of the first edition of The tragedy of man

bears the year of 1861, the volume was in fact published on 12 January 1862.

These first 1500 copies were not sold by booksellers, but distributed among the

supporting members of the Kisfaludy Society as complimentary volumes.

Madách received 20 copies. Given the strong interest, the first edition was

followed already in 1863 by the second, heavily revised version, the last

edition in Madách’s life. In this text Madách took into account not only Arany’s,

but also Károly Szász’s suggestions. The literature, following the principle of

the ultima manus, considers this version as the final text of the

dramatic poem. The Tragedy was published several times after Madách’s

early death (1864), and in 1923, on the centenary of the poet’s birth the first

critical edition was also published by Vilmos Tolnai: “Madách Imre:

Az ember tragédiája. Centenáriumi kiadás. Sajtó alá rendezte Tolnai

Vilmos. Budapest, 1923.”

Vilmos Tolnai (1870–1937), linguist, literary historian, member of the

Hungarian Academy of Sciences, and a professor at the University of Pécs, worked

from Madách’s original manuscript, and carried out a very thorough and exemplary

work. In the preface he summarized his publishing principles: “In the authentic

and true publication of the text, we used the second edition of 1863, as the

final and definitive text published in the poet’s life. We have only corrected a

few letters and punctuations where we saw an obvious typographical error, as

Gedeon Mészöly

1

did in the Rózsavölgyi edition of 1922. We also considered as a typographical

error those plaaces where the missing or superfluous punctuation corrupted the

verse, and the manuscript or the edition of 1861 provides a better reading.”

2

Tolnai’s principles have remained valid up to this day, they laid the

fundamentals of the Madách textology.

Vilmos Tolnai (1870–1937), linguist, literary historian, member of the

Hungarian Academy of Sciences, and a professor at the University of Pécs, worked

from Madách’s original manuscript, and carried out a very thorough and exemplary

work. In the preface he summarized his publishing principles: “In the authentic

and true publication of the text, we used the second edition of 1863, as the

final and definitive text published in the poet’s life. We have only corrected a

few letters and punctuations where we saw an obvious typographical error, as

Gedeon Mészöly

1

did in the Rózsavölgyi edition of 1922. We also considered as a typographical

error those plaaces where the missing or superfluous punctuation corrupted the

verse, and the manuscript or the edition of 1861 provides a better reading.”

2

Tolnai’s principles have remained valid up to this day, they laid the

fundamentals of the Madách textology.

Tolnai in his footnotes took into account all textual versions and changes

“which the manuscript and the two first editions show up. There are the notes

and corrective suggestions of Arany, as well as the adjustments by Károly Szász.”

3

As he did not hesitate to take the original manuscript in hand, he was aware

that Arany’s corrections were largely orthographical in nature, “since the

spelling of Madách did not follow the rules of the Academy but an older

orthography; however, he showed great consistency in that.”

4

We know from Tolnai himself, that the volume published for Christmas 1923 was

completely sold out in four weeks, so in 1924 a new edition became necessary,

whose text was further improved by Tolnai.

However, even the first critical edition did not put an end to the debate as to

which textual version is to be considered the authentic text of the Tragedy.

In 1934 it was published again in the edition of Pál Gulyás. Gulyás in several

places ignored the corrections of Arany, and restored the original text of

Madách. Vilmos Tolnai criticized Gulyás’ procedure, saying that the 1863 text

was approved by Madách, and that the poet’s intentions should be respected.

In the large number of popular editions the text of the Tragedy almost

inevitably deteriorated further: besides errors of punctuation, rhythm and

spelling it also occurred that for verses were missing, and twice two other

verses were reversed.

5

In the 1960s and 1970s the debate flared up again on the authentic text of the

Tragedy. In 1972, on Madách’s 150th birthday the dramatic poem was

published in the edition of József Szabó, a Madách collector in Balassagyarmat.

Szabó in nine places ignored the corrections of János Arany, and restored the

original versions by Madách. From this point, two textual versions of the

Tragedy lived side by side.

6

The historian of literature and theater Ferenc

Kerényi Ferenc (1944–2008) dedicated all his life to the research of

19th-century Hungarian literature. His research focused on Sándor Petőfi and

Imre Madách, he published an excellent monograph on both of them. Ferenc Kerényi

did not belong to those authors who fabricate elaborate theories at the desk,

but picked up the original manuscripts and sources, and based his work and his

conclusions on them. We can consider it natural that it was him to receive

commission for the preparation of the second critical edition, since his great

text edition of 1989, prepared together with Károly Horváth, the Selected works

of Imre Madách was completed with the high standard of the critical

editions: the two excellent researchers established the authoritative text of

the Tragedy with an in-depth knowledge of all textual versions.

In 1995 Károly

Horváth died, thus Kerényi started alone the great enterprise. He invited as his

colleague the forensic handwriting expert József Wohlrab (1952–2012).

Wohlrab had already applied his special expertise in the territory of

literature, by reconstructing the texts of János Arany’s The death of Buda

and Ferenc Kölcsey’s The beautiful Lenka, but these were minor works.

Wohlrab did not exaggerate when claimed about his expert assesment of the Tragedy

that “the cooperation of textology and forensic science on such a large text is

unprecedented..”

7

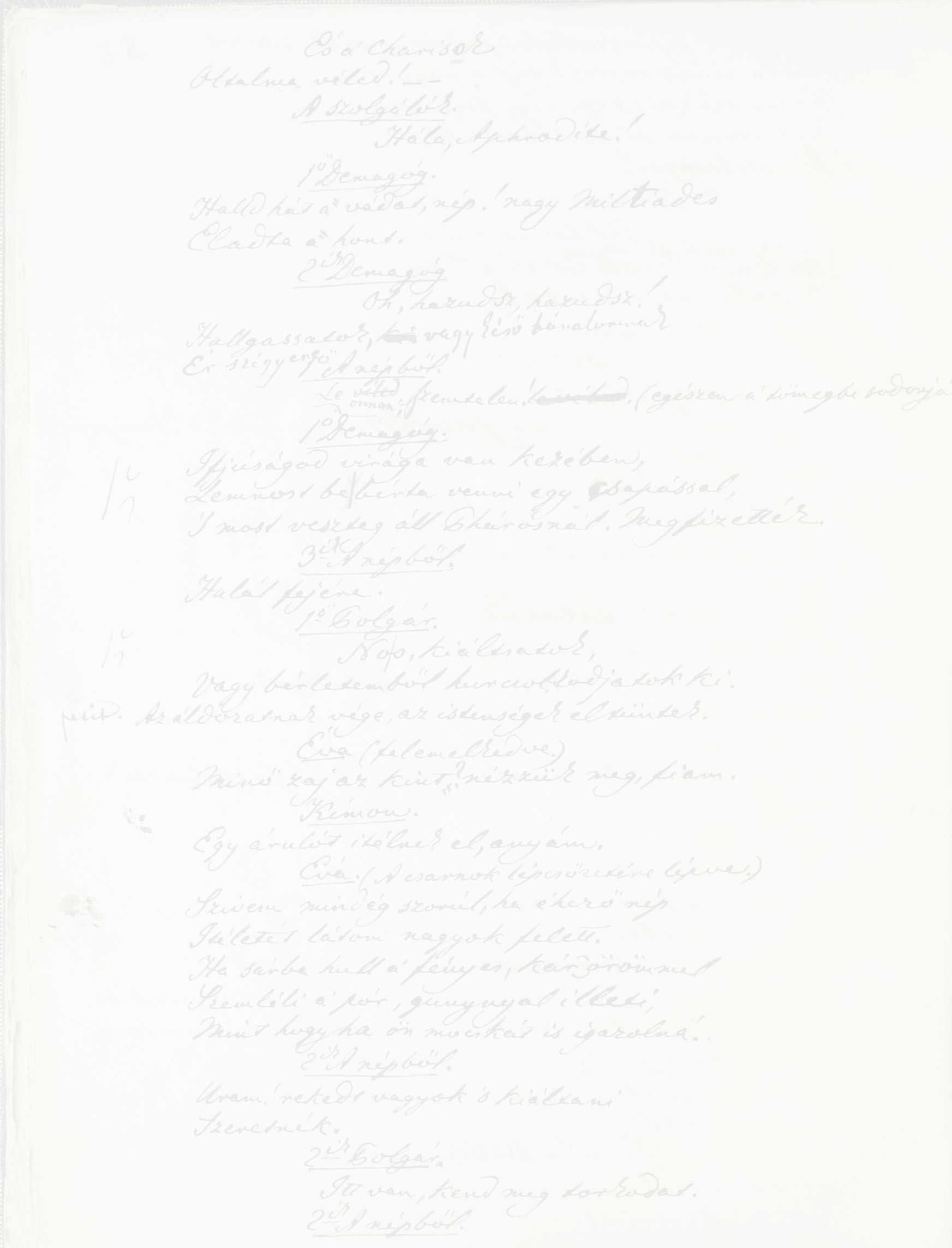

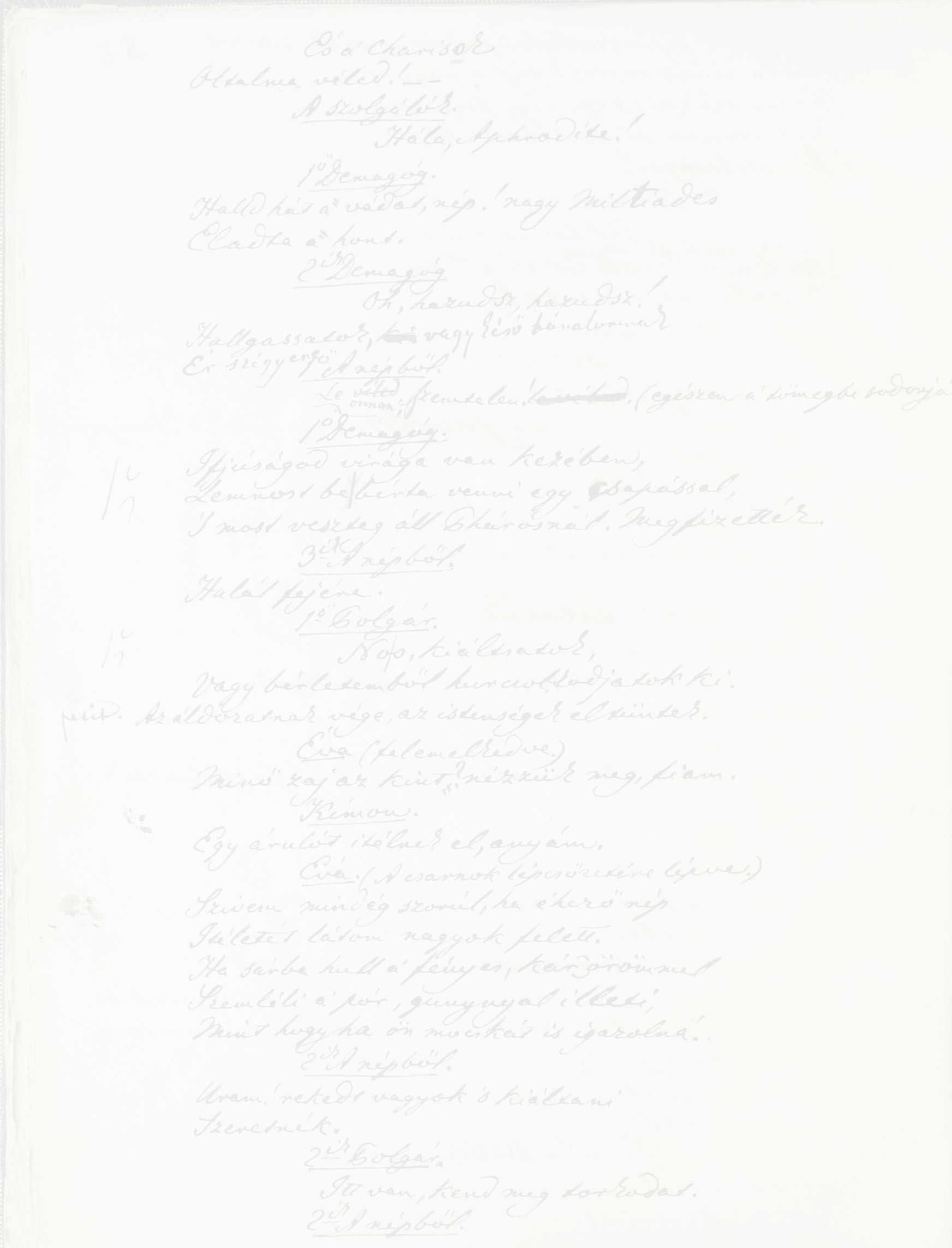

Kerényi considered the work of Hans Walter Gabler, Wolfhard Stoppe and Claus Melchior munkáját,

the three-volume synoptic critical edition of James

Joyce’s Ulysses (1984) as his model to follow. He took into account four

textual versions: Madách’s original manuscript (K), the corrections of the

original manuscript by Arany and Madách (K1), the first edition of 1861 (61), as

well as the second edition of 1863, corrected by both Madách and Károly Szász (63).

He provided these with very detailed notes.

With the work of nearly four years,

8

and with the most state-of-the-art methods of forensic sciences, Ferenc

Kerényi and József Wohlrab examined the complete manuscript of the Tragedy

to a previously unimaginable depth. The colored images made with microscope and

polarizing filters even revealed when Arany, following Madách’s hand, overwrote,

thickened or stressed the faint lines. They showed out not only that Madách used

eight quills,

9

but they even managed to determine where he changed or cut back the pen. Thanks

to the modern technology, a philologically unimportant, but otherwise extremely

interesting thing has become apparent: the fingerprint of Madách on page 42 of

the original manuscript, in Scene 6.

10

Although the manuscript of the Tragedy went through several hands, this

fingerprint certainly belongs to Madách, as “the pigment detectable in the

ridges of the skin are identical with the material of the ink used by the author…”

11

Let us see at a glance the numerical results of Kerényi’s and Wohlrab’s inquiry:

825 corrections are by the hand of Imre

Madách, and 5718 by that of János Arany. This latter is a huge number, which

could eventually justify the opinion of those who want to paint Arany as a

co-author of the Tragedy. But the devil is in the detail this time, too. 74.3%

of Arany’s corrections were typographical in nature, for example when he linked

the preverbs to the verbs preceded by them. 22.9% of the corrections were of

technical nature, which facilitated the work of the typesetter: he linked the

letters together, completed the abbreviated names of the actors (e.g.: Luci[fer]),

detailed the apostrophes making the reading extremely difficult.

12

These together are

97.21% of the corrections. What about the remaining 2.79%? Madách grew up in a

territory dominated by the Palóc dialect, while Csesztve and Alsósztregova were

inhabited by a Slovak majority. It is thus natural, that some dialectal forms

infiltrated into Madách’s language, and these were changed for their literary

equivalent by Arany. This 2.79% includes, among other, the Germanisms replaced

with more Hungarian-sounding solutions.

The huge work of Ferenc

Kerényi and József Wohlrab proved it factually, that János Arany wrote with no

false modesty, but objectively to Madách about his corrections: “With a few

exceptions, they belong to the external technique.”

13

It was found that there are only five cases, where János Arany introduced a line

into the text. In addition, two of them are stage instructions.

14

In conclusion, we can say, that the examination of Kerényi and Wohlrab made a

point at the end of a hundred and fifty years old debate, since they ultimately

cleared, how much and what was improved by János Arany in the Tragedy.

A personal tragedy of Ferenc

Kerényi is that he could only partially harvest the fruits of this huge work.

The Fate did not give him enough time to the content analysis and evaluation of

the large amount of new information. In his monograph published in 2006 in the

series “Memory of Hungarians” of the Kalligram Publisher in Bratislava he

shortly summed up the corrections which came to light as a result of the

handwriting expert’s examination, but a thorough content analysis was still

behind. This was prevented by his premature and unexpected death in 2008.

The large documentation of József

Wohlrab’s examination is preserved in the Manuscript Department of the Library

of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences.