In the nineteenth century, the two most important institutions of Hungarian

cultural life were the Learned Society – today, the Hungarian Academy of

Sciences – and the Kisfaludy Society. Both regularly advertised competitions to

encourage Hungarian science and literature: this is how many classic works of

our literature came to life. It is enough to think about the Toldi,

presented by János Arany to the Kisfaludy Society in 1846.

In the nineteenth century, the two most important institutions of Hungarian

cultural life were the Learned Society – today, the Hungarian Academy of

Sciences – and the Kisfaludy Society. Both regularly advertised competitions to

encourage Hungarian science and literature: this is how many classic works of

our literature came to life. It is enough to think about the Toldi,

presented by János Arany to the Kisfaludy Society in 1846. The Man and woman is no original work, but a romantic-minded

re-elaboration of Sophocles’ Women of Trachis. The actors, the scene, the

plot are all borrowed from Sophocles, but the romantic approach is already

foreshadowed by the motto taken from E. T. A. Hoffmann: “The man is also great

without a woman.” The literature consistently believes that the Man and woman

was written by

Madách in 1842,

8

when he also worked on his treatise on Sophocles, the Art treatise. In

this he also treated the Women of Trachis, and the knowledge gained from

his theoretical studies took on a literary form in the Man and woman.

The Man and woman is no original work, but a romantic-minded

re-elaboration of Sophocles’ Women of Trachis. The actors, the scene, the

plot are all borrowed from Sophocles, but the romantic approach is already

foreshadowed by the motto taken from E. T. A. Hoffmann: “The man is also great

without a woman.” The literature consistently believes that the Man and woman

was written by

Madách in 1842,

8

when he also worked on his treatise on Sophocles, the Art treatise. In

this he also treated the Women of Trachis, and the knowledge gained from

his theoretical studies took on a literary form in the Man and woman. In 1840 the frail Madách traveled to Pöstyén, to find healing in the famous spa

resort. From there he visited the nearby picturesque castle of Trencsén. He

described his impressions in emotionally heated words to his friend Menyhért Lónyay:

“I have visited its collapsed halls, the barren balconies covered with ivy, from

where once the flags of Csák fluttered to advertise freedom. I have seen the

monstrous shadow of the watchtower, from which the gray-heared heroes looked

down with eagle’s eyes, watching over the interests of their homeland… And now

the virtue, the valor, the love for the homeland are all in ruins, only the

mountain eagle makes nest for itself on the collapsed beams.”

14

In 1840 the frail Madách traveled to Pöstyén, to find healing in the famous spa

resort. From there he visited the nearby picturesque castle of Trencsén. He

described his impressions in emotionally heated words to his friend Menyhért Lónyay:

“I have visited its collapsed halls, the barren balconies covered with ivy, from

where once the flags of Csák fluttered to advertise freedom. I have seen the

monstrous shadow of the watchtower, from which the gray-heared heroes looked

down with eagle’s eyes, watching over the interests of their homeland… And now

the virtue, the valor, the love for the homeland are all in ruins, only the

mountain eagle makes nest for itself on the collapsed beams.”

14

Madách sent The last days of Csák to the drama competition of the

Academy. From the note on the cover we know that the manuscript arrived at Pest

on 19 March 1843.

The jury, composed by András Fáy, József Bajza, Gergely Czuczor,

Ferenc Schedel and Mihály Vörösmarty met on 4 October 1843. Károly Obernyik’s

Aristocrat and peasant was awarded. Ede Szigligeti’s Gerő was found

worthy for publication, but they also noticed Madách’s work: “Thereafter, we

must highlight with praise… The last days of Csák, a drama in five acts.”

15 Mór Jókai’s The Jewish boy was also praised.

16

From a letter by

Madách to János Arany on 3 October 1861 we know, that eighteen years after the

competition, in August 1861 he took out again and rewrote The last days of

Csák: “Here I enclose a play.

17 By no means wanted I depict Máté Csák in all his magnitude, which

Károly Kisfaludy failed to do; I only wanted to show the dying lion in his last

days. I don’t know, however, whether I succeeded in doing so, and whether this

simple plot could have any effect on the stage. (…) I ask you therefore (…)

to judge my work, not only its inherent value, but also whether it is suitable

for the stage, because I know how difficult and how special it is to meet this

requirement. –

If appropriate, be so kind to present it to the jury of the

dramatic competition; if not, send it back to me. (…) The reason why I

chose among my works this play for a complete elaboration, is partly my special

interest in the subject, and partly that the name of Máté Csák has started to

revive in our literature, and I, to avoid any involuntary imitation, did not

even dare to read Károly Szász’s Csák, only today I start it – this is why I

hastened to prepare mine.”

18

Madách formulated it precisely: in our 19th-century literature the name of Máté

Csák started to “revive”, because his historical role was judged diametrically

oppositeto how he was considered in the 20th century or nowadays. Today he is

alive in the public imagery as he was depicted in Ady’s poem On the land of

Máté Csák: the symbol of the domineering feudal lord. However, in the 19th

century, the reform era and in the time of absolutism “the name of Máté Csák was

linked to national independence and the efforts of freedom against the

foreigners.”

19

This widespread evaluation was based on the fact that Máté Csák supported

Elisabeth, the daughter of Andreas III, the last king from the Árpád dynasty,

against Robert Charles, the king of foreign origins. Károly Kisfaludy dedicated

him two incomplete works in this spirit, the Zách family and Csák. Petőfi

planned to write an epic on him,

20

and Arany had the same idea.

21

His name is repeatedly mentioned in Vörösmarty’s works, too, who also wrote a

German-language epic poem entitled Csák.

22

In

1861, as it is attested by the letter of Madách, Károly Szász wrote a narrative

poem on Csák of Trencsén.

Madách’s choice of topic, however, was motivated not only by the spirit of the

age, but also by personal feelings, since one of his ancestors served as a

soldier in the time of Andreas III.

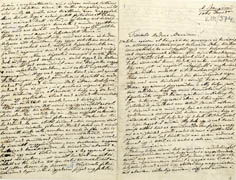

In October 1861 János Arany enthusiastically supported the publication of The

tragedy of man, but the second, reworked version of Csák did not please him.

He believed, it is more advantageous to Madách if “Csák is not known until they

read the Tragedy. I find so that in this latter, in spite of the actors’

representing abstract ideas, there is more drama than in the Csák. But let us

return to this on another occasion.”

23

Madách understood the delicate words, and in his answer he urged János Arany to

a radical action: “From your short note on The last days of Csák I

understand that it has no drama. Which is no little trouble in drama! There is

no greater calamity than the survival of a mediocre work. It will come forth, if

not in our life, then after our death, when a heartless good friend would

compromise us with it. So please, throw it into fire, but I would be happy to

hear some of your observations after the autodafé, because I could learn

from them. All I am writing now is my sincerest conviction: I would not consider

myself worthy of your friendship if I wanted to show myself different than I am

in your eyes, just as I always wait the straightest truth from you: what is

more, the more brutal and the farther it is from your very mild observation on

Csák, the more I see that you love me.”

24

(35 MTAK K 13/374)

In October 1861 János Arany enthusiastically supported the publication of The

tragedy of man, but the second, reworked version of Csák did not please him.

He believed, it is more advantageous to Madách if “Csák is not known until they

read the Tragedy. I find so that in this latter, in spite of the actors’

representing abstract ideas, there is more drama than in the Csák. But let us

return to this on another occasion.”

23

Madách understood the delicate words, and in his answer he urged János Arany to

a radical action: “From your short note on The last days of Csák I

understand that it has no drama. Which is no little trouble in drama! There is

no greater calamity than the survival of a mediocre work. It will come forth, if

not in our life, then after our death, when a heartless good friend would

compromise us with it. So please, throw it into fire, but I would be happy to

hear some of your observations after the autodafé, because I could learn

from them. All I am writing now is my sincerest conviction: I would not consider

myself worthy of your friendship if I wanted to show myself different than I am

in your eyes, just as I always wait the straightest truth from you: what is

more, the more brutal and the farther it is from your very mild observation on

Csák, the more I see that you love me.”

24

(35 MTAK K 13/374)

The response of

Madách reveals several things. First, how great authority Arany was to him, and

second, how rigorous critic he was of himself.

The sober, not quick-tempered Arany of course did not throw into the fire the

drama of Madách: “We should never hurry with the autodafé of Mr. Csák. I will

tell you if it is necessary: but it is not yet. Let us return to it later, when

I will have the time and mood.”

25

To the reception of The last days of Csák belongsthat in 1969 it

was published in a “reformed”, “modernized” language by Dezső Keresztury.

26

(Csák végnapjai (The last days of Csák). Drama in five acts. With a

foreplay in one act.

A competition work for 1843. LHAS Department of Manuscripts, Magyar Irodalom Színművészet 4°

20/173.)

Mózes

From Madách’s flyleaf to Moses we know that he wrote his play between 9 July

1860 and 16 November 1861.

27

In this period he was extremely busy, working on more than one work: in the

autumn of 1861 he reworked his play The last days of Csák, and he was in

correspondence with János Arany on the corrections of the Tragedy.

From Madách’s flyleaf to Moses we know that he wrote his play between 9 July

1860 and 16 November 1861.

27

In this period he was extremely busy, working on more than one work: in the

autumn of 1861 he reworked his play The last days of Csák, and he was in

correspondence with János Arany on the corrections of the Tragedy.

The circumstances of the presentation of Moses we know from his letter to

his friend Iván Nagy from 23 December 1861: “I had great problems with it.

First, I was late in writing it, so I could hardly finish it, and then I had no

time to let it rest a couple of months, when I myself can better judge whether

it is worthy to be sent for the competition. – But now, when hardly

completed, I already had to cause it copied, now, when I still feel the ecstasy

which, I think, every author feels for his own work immediately after completing

it, just like the man in love at the first embraces of the conquered lady. As a

result, I am truly terrified whether I send a failed work. (…) My troubles

are increased by the fact that it was copied in a scandalous script, which

deters from reading and gives an unfavorable impression.”

28

Madách was pressed by time: there was little more than a week until the deadline

of 31 December, so, although apologetically, but he aske two things of his

friend: first, to bind the manuscript, “as the rules require”, and second, “not

as an expert, but as an educated public”, “judge it in all opennes, whether it

is worthy to send for the competition or not”.

29

Iván

Nagy considered it worthy to present Madách’s work, which arrived at the

Academy, for the Karátsonyi drama competition on 29 December 1861.

It is amazing, how strong Madách was, how easily could renounce of his work and,

as a fatalist, to leave on his friend’s decision the fate of his spiritual

child. If Iván Nagy happened to feel that the Moses is a failed work, and

does not present it on the competition, now we would be poorer of a work by

Madách.

The “committee report” was read by corresponding member Károly Bérczy on the

meeting of 31 March 1862. The manuscript of the report has survived, and also

published in print in the secondvolume of the 1861/2 edition of the Magyar Akadémiai Értesítő,

which, in spite of its numbering, was publishe in 1862.

The report revels that six works were sent to the competition, whose jury was

composed by Baron Zsigmond Kemény, János Arany, Mór Jókai, János Pompéry, and

Károly Bérczy. Among the members of the jury, Madách was on good terms with

Károly Bérczy, and since a few months he had also enjoyed the confidence of

János Arany. Nevertheless we can say in full certainty that these acquaintances

did not bring any benefit to Madách, since he sent the Moses anonymously,

and it was not his drama which won the first prize. From his letter to Iván Nagy

we know that he counted with this possibility, and he acted with an

exemplary care and honor: “I would have willingly sent it [that is, the Moses]

to János Arany, to judge whether it is worthy for the competition. I know his

special friendly inclination shown towards me could have allowed it. But there

is no time for that, and I was also afraid that he might be a member of the

jury, so he must not know about this work..”

30

The feeling of

Madách was justified: János Arany was also a member of the jury.

The jury did not conceal that they were unsatisfied with the level of the works:

“the report should start with the reservation that the award has been given to

this and this work not because it is definitely good, or because

it is the best among the good competitors – but because it is relatively better

than the other, weak ones.” The literature links the criticism to the name

of Károly Bérczy, although he probably only summed up, poured in its final form,

read and published the judgment of the jury, but the text itself is based on the

thoughts of others.

On the Moses the report tells the following: “The fourth work is

Moses, called a tragedy in five acts, although it is essentially no tragedy,

and not even a drama. Moses is a purely epic subject, and as presented, he is an

epic, and no tragic figure. He is the first warrior of his people; he follows

the voice of fate; his task is to fulfill the common interest, and not his own

individual goal, for which the hero of the tragedy comes into conflict with the

order of the world, to finally fall fighting. Moses, on the contrary, receives

his vocation from God, and he is supported by divine force. He is a fatal hero:

he himself says that he cannot fall until he fulfills his vocation. –

But he is also an epic hero because he leads his people to victory through every

vicissitude; because the fact that he cannot enter the land of promise, only

look into it, is no tragic fall, it is almost as much as if he entered it. And

finally, he is no tragic hero also because he has no tragic errors. He himself

does not feel anything like this, on the contrary, in his final hour he

courageously says:

“My soul is not charged by any accusation.”

This is not how the hero of a tragedy dies. This latter usually dies by wishing

to start his career again, and, learning from his mistakes, to run it better

than for the first time.”

33

The competition was won by the play number five. From the letter by Károly Szász

written on 12 September 1862 we know that the criticism published in the Akadémiai Értesítő

was accepted by Madách with dignity and understanding. “I do not belong to them

who close their ears from criticism. This year I participated at the drama

competition with my Moses, and the opinion of the jury convinced me about

the mistaken principles of my work so much, as if it were a foreign work.”

34

A day later he wrote in similar words and in the same spirit to János Erdélyi:

“…this year, the well-founded judgement of the jury of the Teleki

35

drama competition convinced me so much about the mistaken principles of my work

that it will never again see the light of day.”

36

However, he was wrong in the last sentence. The Moses has been

published several times, and it was a success on the stage, too. In the 1970s

and 80s it was played in the National Theatre in a language modernized by Dezső

Keresztury, and in one and half decade it had almost five hundred sold-out

presentations.

(Mózes (Moses). Tragedy in five acts. Work presented for the Karátsonyi

drama competition in 1862.

LHAS Department of Manuscripts, Magyar Irodalom Színművészet 4° 35/A. 299.)