Madách worked on the Tragedy since 17 February 1859, almost secretly,

so that none

of his family members and close friends were aware of the work in preparation.

However, after he completed it on 26 March 1860,

1

like every artist, he also had the natural desire to “show himself”, to seek the

opinion of others. He first read the Tragedy to Pál

Szontagh (1820–1904) in the spring of 1860.

2

This prominent figure of the aristocratic opposition in Nógrád county had been linked by

ties of friendship to Madách since the 1840s, and since the 1850s he had lived in Horpács, next to Alsósztregova. Szontagh and Madách regularly met, thus it was

obvious that Madách trusted him. However, as a friendly opinion could be more

partial than that of an outsider, therefore Szontagh urged Madách

3

to send the Tragedy to János Arany for criticism. The author of Toldi

was the unquestioned literary authority of the period, and his word had the most

weight.

Madách worked on the Tragedy since 17 February 1859, almost secretly,

so that none

of his family members and close friends were aware of the work in preparation.

However, after he completed it on 26 March 1860,

1

like every artist, he also had the natural desire to “show himself”, to seek the

opinion of others. He first read the Tragedy to Pál

Szontagh (1820–1904) in the spring of 1860.

2

This prominent figure of the aristocratic opposition in Nógrád county had been linked by

ties of friendship to Madách since the 1840s, and since the 1850s he had lived in Horpács, next to Alsósztregova. Szontagh and Madách regularly met, thus it was

obvious that Madách trusted him. However, as a friendly opinion could be more

partial than that of an outsider, therefore Szontagh urged Madách

3

to send the Tragedy to János Arany for criticism. The author of Toldi

was the unquestioned literary authority of the period, and his word had the most

weight. In the spring of 1861 Madách had the opportunity to let his work get to Arany.

As one of the parliamentary deputies of Nógrád county, Madách came to the

national assembly, opened on 6 April 1861 in Pest, and brought with himself the

only, handwritten copy of the Tragedy. We have no irrefutable evidence

that Madách met Arany, but on the basis of indirect data both their

contemporaries and Ferenc Kerényi

4

– one of the best Madách researchers of the past decades – have been

inclined to think that Madách personally handed over his work. Kerényi also

risks the assumption that the meeting took place on 5 June 1861, after Madách’s

highly successful parliamentary speech. Concerning the parliament’s answer to be

given to Emperor Francis Joseph, Madách represented the opinion of the

Resolution Party, led by László Teleki. According to Kerényi, his speech might

have provided him with enough confidence to visit Arany in his home at Üllői

street. Madách’s obituary published in the Koszorú, the journal of János Arany

recalls the meeting in the following words: “[Madách] asked his fellow deputy

Pál Jámbor to take him to Arany, to whom he would like to hand over a work for

criticism. Pál Jámbor fulfilled his wish. Arany accepted the work from the

unknown poet, who asked him for a sincere opinion, and spoke little during the

whole visit.”

5

According to Ferenc

Kerényi, the “U” signature of the above obituary points to Pál Gyulai, whose

information – being one of János Arany’s most confidential friends – certainly

came from first hand.

In the spring of 1861 Madách had the opportunity to let his work get to Arany.

As one of the parliamentary deputies of Nógrád county, Madách came to the

national assembly, opened on 6 April 1861 in Pest, and brought with himself the

only, handwritten copy of the Tragedy. We have no irrefutable evidence

that Madách met Arany, but on the basis of indirect data both their

contemporaries and Ferenc Kerényi

4

– one of the best Madách researchers of the past decades – have been

inclined to think that Madách personally handed over his work. Kerényi also

risks the assumption that the meeting took place on 5 June 1861, after Madách’s

highly successful parliamentary speech. Concerning the parliament’s answer to be

given to Emperor Francis Joseph, Madách represented the opinion of the

Resolution Party, led by László Teleki. According to Kerényi, his speech might

have provided him with enough confidence to visit Arany in his home at Üllői

street. Madách’s obituary published in the Koszorú, the journal of János Arany

recalls the meeting in the following words: “[Madách] asked his fellow deputy

Pál Jámbor to take him to Arany, to whom he would like to hand over a work for

criticism. Pál Jámbor fulfilled his wish. Arany accepted the work from the

unknown poet, who asked him for a sincere opinion, and spoke little during the

whole visit.”

5

According to Ferenc

Kerényi, the “U” signature of the above obituary points to Pál Gyulai, whose

information – being one of János Arany’s most confidential friends – certainly

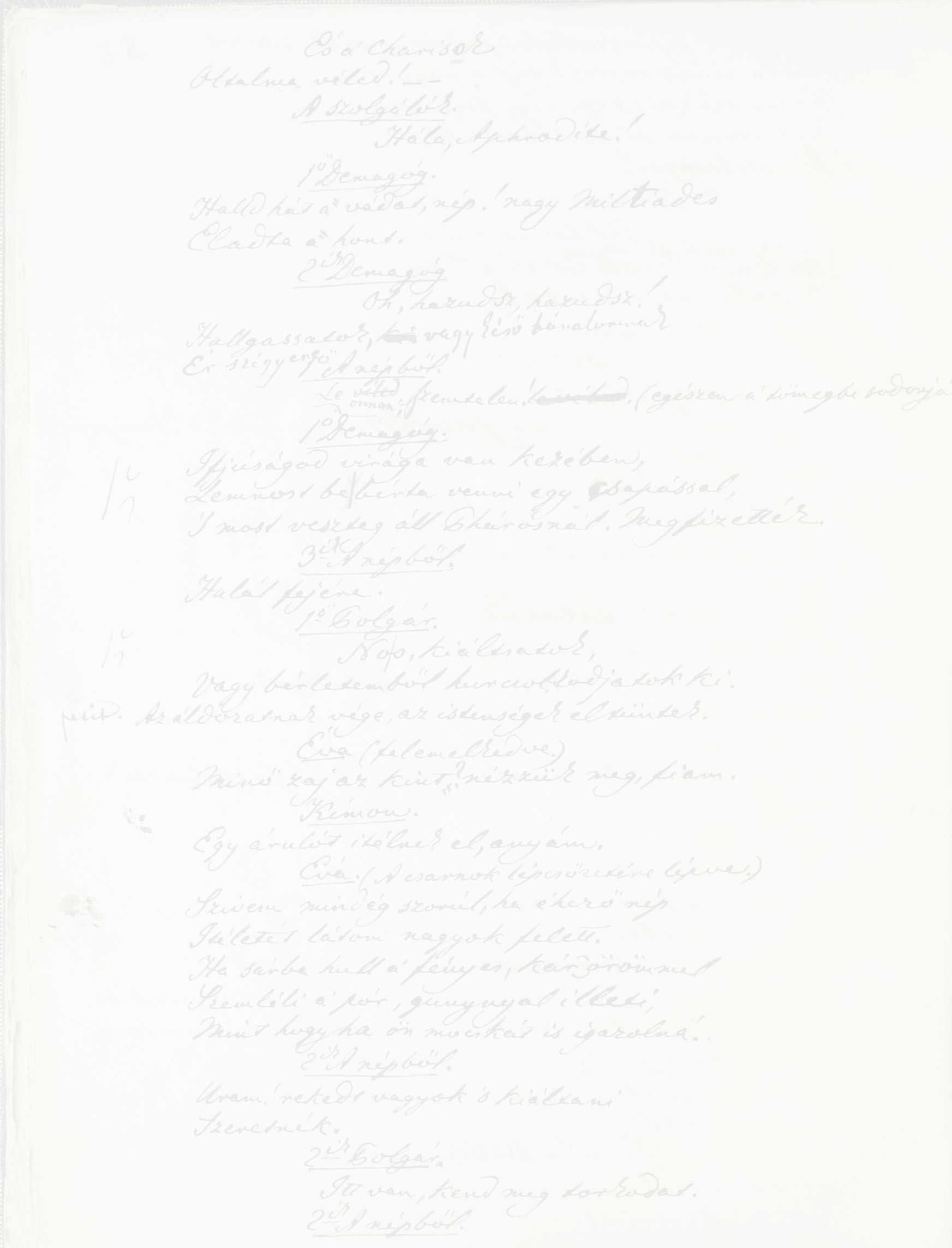

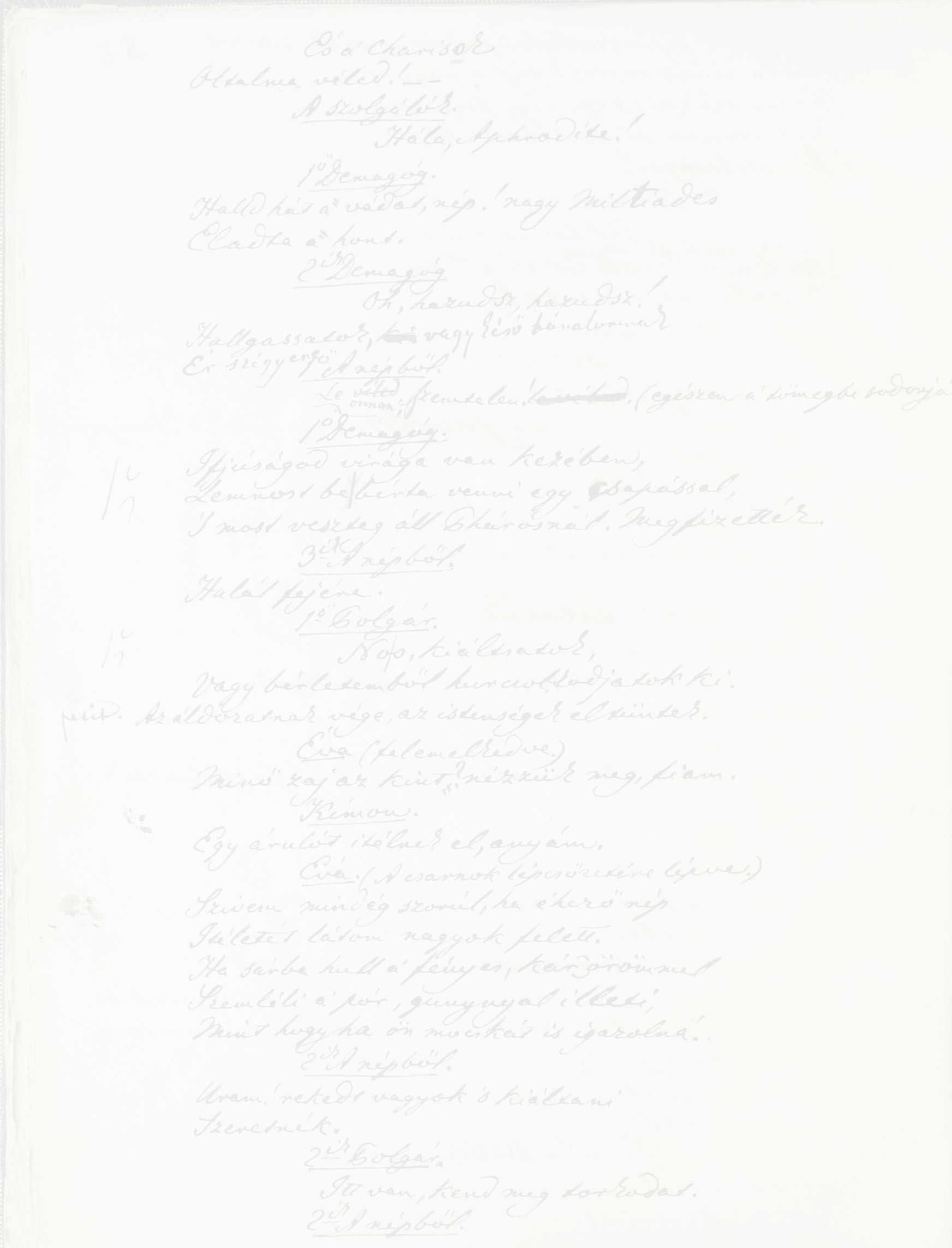

came from first hand. Arany soon began to read the Tragedy but he did not like it, as after

some lines he suspected it to be an afre-feeling of the Faust. The first

Hungarian translation of Goethe’s masterpiece had been published a year ago,

6

thus the suspicion of Arany was legitimate. In his letter of 27 October 1861 to

Madách, summarizing his suggestions and corrections, he commented the following

words of Lucifer in Scene 2: “You elements, Lend aid, arise–– Humanity Will be your prize.––” like this: “…it is like Goethe, in István Nagy’s

translation.”

7

Arany soon began to read the Tragedy but he did not like it, as after

some lines he suspected it to be an afre-feeling of the Faust. The first

Hungarian translation of Goethe’s masterpiece had been published a year ago,

6

thus the suspicion of Arany was legitimate. In his letter of 27 October 1861 to

Madách, summarizing his suggestions and corrections, he commented the following

words of Lucifer in Scene 2: “You elements, Lend aid, arise–– Humanity Will be your prize.––” like this: “…it is like Goethe, in István Nagy’s

translation.”

7

After the dissolution of the parliament, Madách came home to Alsósztregova on 1

September 1861, and was obviously looking forward with impatience to a sign from

the senior fellow poet. Arany sent his famous letter with the address “Dear

Patriot!” on 12 September: “The tragedy of man is an excellent work

both in its conception and composition. I only find some ponderosity here and

there in its poesy and its language; especially the lyric parts are not sonorous

enough. But even like this, after some external touches, it could occupy a place

among the most excellent works of our literature. I do not know what are your

intentions as to its publication: I would wish to promote it through the

Kisfaludy Society, and I hope I would succeed in doing so. If my wish met your

will, then I would mark the places, from line to line, where I would suggest

some – but by no means essential – changes; or if you agree, I myself would add

to it a few pen strokes, and then I would present it to the Society.”

10

After the dissolution of the parliament, Madách came home to Alsósztregova on 1

September 1861, and was obviously looking forward with impatience to a sign from

the senior fellow poet. Arany sent his famous letter with the address “Dear

Patriot!” on 12 September: “The tragedy of man is an excellent work

both in its conception and composition. I only find some ponderosity here and

there in its poesy and its language; especially the lyric parts are not sonorous

enough. But even like this, after some external touches, it could occupy a place

among the most excellent works of our literature. I do not know what are your

intentions as to its publication: I would wish to promote it through the

Kisfaludy Society, and I hope I would succeed in doing so. If my wish met your

will, then I would mark the places, from line to line, where I would suggest

some – but by no means essential – changes; or if you agree, I myself would add

to it a few pen strokes, and then I would present it to the Society.”

10

“It’s done, the great act of creation.

“It’s done, the great act of creation. One

adage, however, was associated with Arany’s name without any basis. There were

theater directors who omitted the famous final verse – “Man, I have spoken: strive on, trust, have faith!” – by saying that it was not from Madách. However, even

no polar filter test would have been necessary, only a glimpse at the original

manuscript, to be ascertained of the contrary view! Nevertheless, the

handwriting expert asked for the examination of the manuscript checked the final

verse with x-ray, and it became clear that János Arany did not touch it.

One

adage, however, was associated with Arany’s name without any basis. There were

theater directors who omitted the famous final verse – “Man, I have spoken: strive on, trust, have faith!” – by saying that it was not from Madách. However, even

no polar filter test would have been necessary, only a glimpse at the original

manuscript, to be ascertained of the contrary view! Nevertheless, the

handwriting expert asked for the examination of the manuscript checked the final

verse with x-ray, and it became clear that János Arany did not touch it. especially concerning the few typographical errors which,

with all my efforts, had slid into the publication, as well as on the changes

you have unlimitedly authorized me to, but in which I limited myself to those

already reported to you. I also mentioned that if you are displeased with them,

in a second edition – of which, thank God, will be urgent need soon – you

can restore the original text (your manuscript is still at me, in a usable

condition).

29

especially concerning the few typographical errors which,

with all my efforts, had slid into the publication, as well as on the changes

you have unlimitedly authorized me to, but in which I limited myself to those

already reported to you. I also mentioned that if you are displeased with them,

in a second edition – of which, thank God, will be urgent need soon – you

can restore the original text (your manuscript is still at me, in a usable

condition).

29

In his answer, Madách dispelled Arany’s concerns: “I only owe gratitude for your

changes, and the typographic errors are amazingly few.”

30

In his answer, Madách dispelled Arany’s concerns: “I only owe gratitude for your

changes, and the typographic errors are amazingly few.”

30

In the “second, substantially improved” edition, which was

also published by Gusztáv Emich in 1863, Madách also took his observations into account. As

this was the last edition published in the poet’s life, now this version is

considered the final text of the Tragedy.

In the “second, substantially improved” edition, which was

also published by Gusztáv Emich in 1863, Madách also took his observations into account. As

this was the last edition published in the poet’s life, now this version is

considered the final text of the Tragedy.