The Archaeological Committee of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences,

founde in 1858, set as its goal to prepare a survey of the archives, antiquities

and historical buildings of Hungary.

1

The Committee entrusted Ferenc Kubinyi

2 and Flóris Rómer

3 with the coordination of the work. Kubinyi, a honorary member of

the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, was one of the leaders of the parliamentary

opposition in the Age of Reforms. A lawyer by profession, he suffered several years

of prison because of his engagement in the War of Independence. After his

release, he researched history and archaeology. He returned shortly before the

commission from Istanbul, where he investigated after King Matthias’ disappeared

codices on behalf of the Academy.

The Committee entrusted Ferenc Kubinyi

2 and Flóris Rómer

3 with the coordination of the work. Kubinyi, a honorary member of

the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, was one of the leaders of the parliamentary

opposition in the Age of Reforms. A lawyer by profession, he suffered several years

of prison because of his engagement in the War of Independence. After his

release, he researched history and archaeology. He returned shortly before the

commission from Istanbul, where he investigated after King Matthias’ disappeared

codices on behalf of the Academy.

Flóris Rómer, a Benedictine priest and professor, historian and archaeologist

was still only a corresponding member of the Academy, but his book on the

archaeological monuments of the Bakony mountains, published in 1860, made his

name well-known throughout the country. He was the founder and, from 1861, the

first leader of the Manuscript Department of the Library of the Hungarian

Academy of Sciences.

Flóris Rómer, a Benedictine priest and professor, historian and archaeologist

was still only a corresponding member of the Academy, but his book on the

archaeological monuments of the Bakony mountains, published in 1860, made his

name well-known throughout the country. He was the founder and, from 1861, the

first leader of the Manuscript Department of the Library of the Hungarian

Academy of Sciences.

In August 1862 the two scholars and the architect Károly Bergh went to Nógrád

county, to survey and draw the renowned church and secular buildings of this

region, rich in historical landmarks. What led them to turn, loaded with

valuable drawings and protocols, off the convenient highway and to proceed on a

breakneck secondary road to Alsósztregova? Shortly before that, the Vasárnapi

Újság published the portrait and biography of Imre Madách,

4

and this fresh memory prompted them to salute the bright new star of the

Hungarian literature in his home town.

On their arrival they got to know that recently left the hospitable house János

Arany, who was a guest of Imre Madách on his return from the spa of Szliács.

They had a nice welcome in the castle, which was not surprising, given that

Ferenc Kubinyi was well known all over the county.

During their stay they saw the beautiful, well-kept garden of Madách, the

apparently ancient, but historically rather uninteresting Lutheran church, and

the old castle of the family, which also served as a fortress during the Ottoman

occupation. The Turks destroyed it, and only the grandfather of Imre Madách,

Sándor rebuilt it. During Kubinyi’s and Rómer’s visit it was used as a granary

and the home of the land-steward.

Rómer was especially interested in the neatly organized, cataloged and well-kept

family archive, which in this respect was an exception among the private

archives seen by him. Already in 1857 Imre Madách reported to the secretary of

the Academy, Ferenc Toldy, about the treasures of their family archive – it was

probably then that he cataloged it –, and he even sent a small sample from the

manuscript of the Haazy Apatéka, translated from Czech by one of his

ancestors, Gáspár Madách. (This manuscript was considered important by

bibliographer József Szinnyei.)

After several days of sojourn, they happily and contentedly left Alsósztregova.

Their host accompanied them on horseback to the neighboring Gács. “Who knew

then, that I shook Madách’s friendly hand for the last time?” – wrote later

Flóris Rómer.

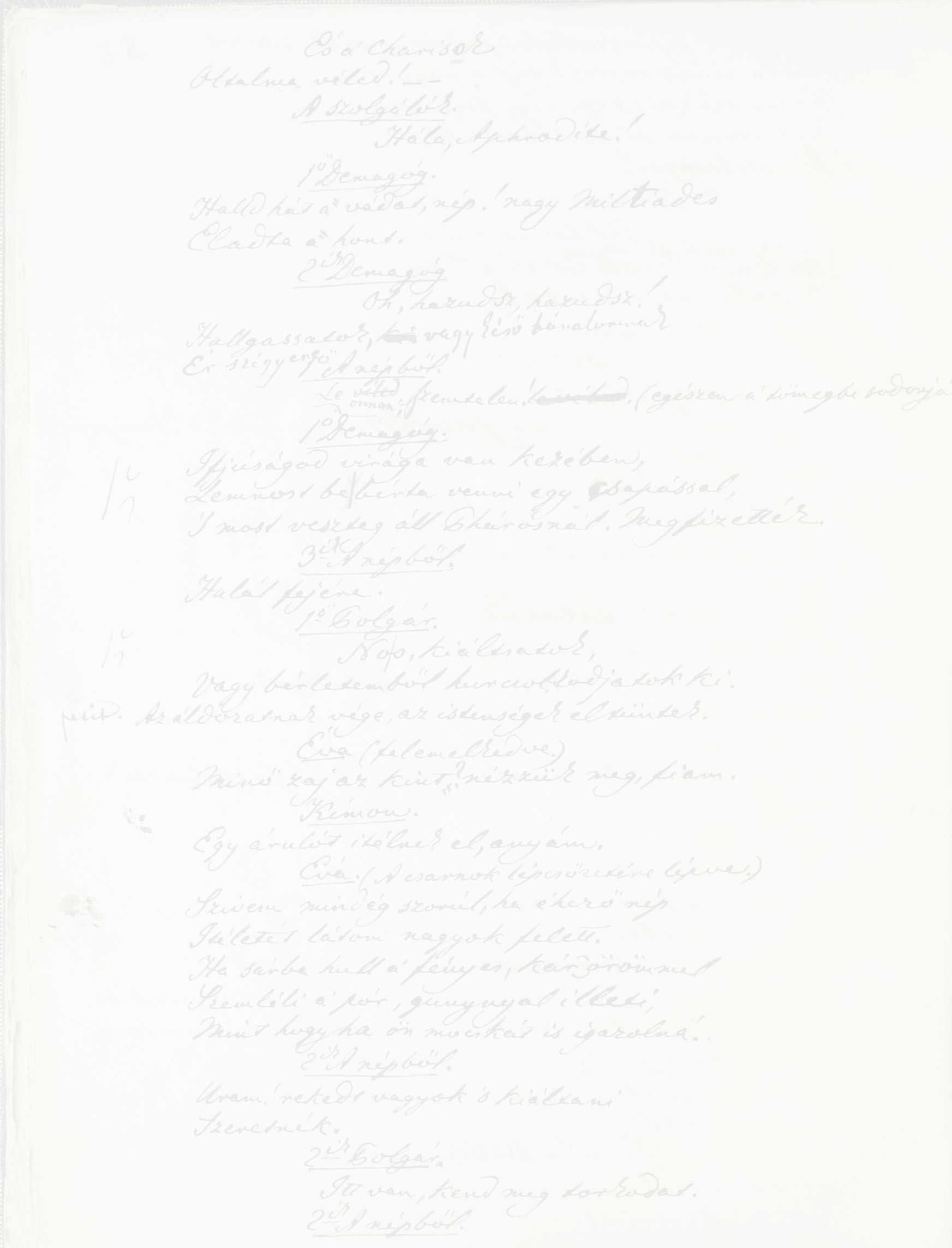

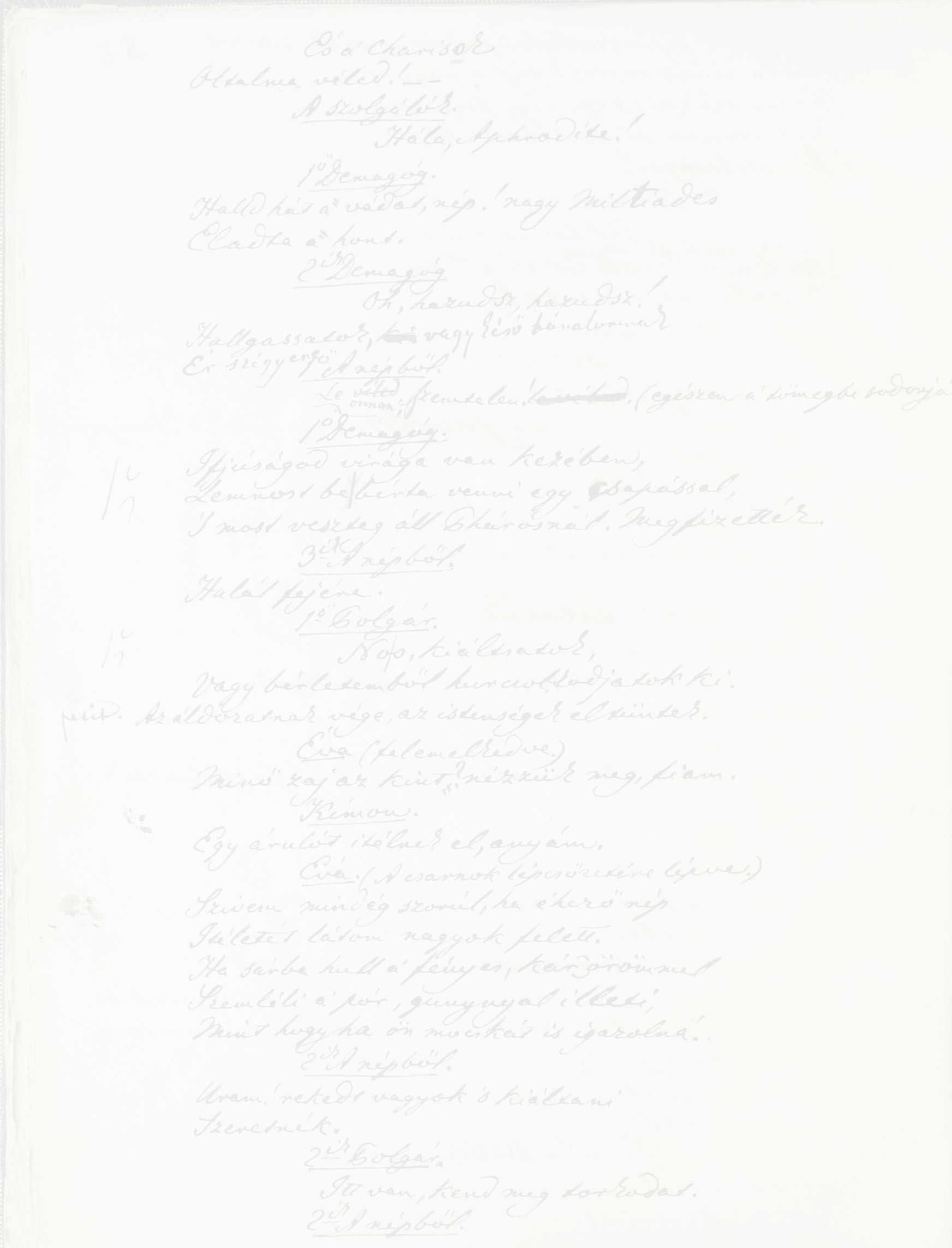

In memory of this visit, Imre Madách gave a very precious gift, an incunabulum

to the Library of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. It was printed in German

territory, with the title Hymni. Expositio hymnorum cum commento.

Hagenau : [Heinrich Gran], 1493. The work was compiled by the 12th-century

theologian Hilarius. Today it is preserved in the Department of Manuscripts and

Rare Books of the Library of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, shelfno. Inc. 383/koll. 1.

Madách wrote a recommendation on the flyleaf of the book: “To the Hungarian

Academy of Sciences recommends this book Imre Madách. In Alsósztregova, on 23

August 1862. In memory of this pleasant day, when I had the luck to pay honor to

my friends Ferenc Kubinyi and Flóris Rómer in my house.”

We do not know how this volume found its way to the Madách library. According to

the possessor entries on the flyleaf and the first page, it first beloned to

Stephanus de Rewa, and in the late 18th century it got to Gáspár Szulyovszky,

probably a member of the town council of Pozsony/Bratislava, who had been a

pupil of Mátyás Bél in the Lutheran lyceum in Bratislava. It was probably

purchased by Sándor Madách, Imre’s grandfather, because it was him to

re-establish the family library, which had been scattered at the time of János

Madách.

5

It is certain that the author of the Tragedy donated one of the most

cherished family treasures to the Library of the Academy. In 1913 the manuscript

legacy and library of Madách got into the Library of the Hungarian National

Museum. József Szücsi, the researcher of the library published its catalog in

the appendix of his study.

6

He ascertained that the library reflects the diligence of three family members:

of Sándor Madách, the poet’s grandfather, of Imre Madách Sr., and of the poet.

The almost 1100 volumes embraced the publications of the period of the

collectors, from the late 18th century to the middle of the 19th century.

Earlier works are rare to find in it.

The donation of Madách was announced in the small assembly of the Hungarian

Academy of Sciences, and in §. 335 of the protocol they accepted it with thanks,

handing it over to the Library of the Academy.

7

Some weeks after receiving news about the death of Madách,

Rómer wrote his memories on their visit to the writer. His article was published

with the title Remembering Imre Madách

in the 10 December 1864 issue of the Vasárnapi Újság.

8

The incunabula, however, was not the only gift of Madách. The writer otherwise

facing continuous financial problems offered 200 forints from the 327.5 forints

honorary of the first edition of The tragedy of man to enrich the capital

of the Academy. On 20 February 1862 he wrote the following to János Arany, whom

he appointed to hand over his donation: “…it was my firm intention to dedicate

my first spolia [acquisitions, here: honoraries] on the altar of the

Muses, so I offered … 200 forints complemented to the capital of the Academy.”

9

It was already among the most important plans of the Academy’s founder István

Széchenyi to establish a building of its own for the Academy. In the Age of

Reforms this could not be realized for various difficulties. In 1858 Baron Simon

Sina, a Greek-born Viennese banker, a member of the board of directors of the

HAS offered 80 thousand forints for the building of the palace of the learned

society. As a result, in 1859 the HAS launched a collection for the construction

of the Academy’s own home. The national donation grew into the most important

social movement of the period between the war of independence and the Compromise

of 1867. Thousands of private people and a multitude of the societies coming

into being after the softening of the authoritarian system sent their donations

to the Academy. The amount coming from the collection – more than 670 thousand

forints – almost entirely covered the costs of construction. The palace of the

Academy, built also with the contribution of Imre Madách, opened its doors in

December 1865, and still stands in the service of Hungarian science.